THE FACT THAT from the mid-1960 onwards fascists and Nazis stepped up their efforts to obtain arms and explosives was no casual matter. The strategy of tension theory was being elaborated— and elaborated openly. In Rome from 3 to 5 April 1965 leading exponents of the right gathered in the Parco dei Principi hotel for a symposium on “Revolutionary Warfare”, organised by the Alberto Pollio Institute of Military History.

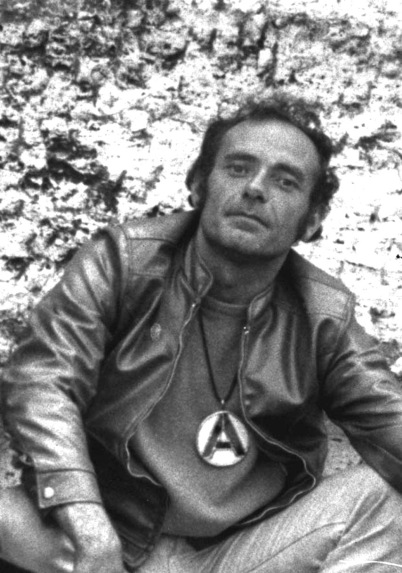

Prominent figures who attended included Ordine Nuovo founder, Pino Rauti; Guido Giannettini, journalist and SID agent; and Edgardo Beltrametti and Enrico De Boccard, two journalists who went on to set up the Nuclei di Difesa dello Stato (State Defence Nuclei). Twenty or so students had also been invited. Among these were two whose names would crop up over and over again throughout those years: Stefano Delle Chiaie (the head of Avanguardia Nazionale) and his pupil, Mario Merlino. [See La Storia Siamo Noi – L’inchiesta su Ordine Nuovo – Piazza Fontana]

While Rauti and Giannettini’s contributions drew applause, it was the university lecturer and Orientalist, Pio Filippani Ronconi, a cryptographer with the Defence Ministry and the SID who electrified the audience. The papers read at the symposium were published later that year as La guerra rivoluzionaria by the Gioacchino Volpe publishing house. The book enjoyed what was essentially a “militant” readership among the various far right groups. For instance, Paolo Molin from took a copy to show to Ordine Nuovo activists in Venice, including the members of the cell run by Delfo Zorzi.

The topic of the Parco dei Principe symposium was the appropriate short-term strategy to be adopted in the face of perceived communist advances and to keep Italy within the western orbit. In his paper “Hypothesis for a Revolution”, Filippani Ronconi suggested a security organisation structured on various levels — operational as well as hierarchical. The grassroots would be professionals — teachers and small industrialists — people capable of carrying out only wholly passive and non-risky activities, but the sort of people in a position to boycott communist promoted initiatives.

The next level consisted of people capable of “bringing pressure to bear” through lawful demonstrations: these were people who would rally to the defence of the State and of the laws.

“At the third, more skilled and professionally specialised level” Filippani Ronconi argued, “would be the very select and hand-picked units (set up anonymously and immediately) trained to carry out counter-terror and possible ‘upsets’ at times of crisis to bring about a different realignment of forces in power. These units, each unknown to each other, but coordinated by a leadership committee, could be recruited, partly, from among those youngsters who were currently squandering their energies to no effect in noble demonstrative ventures.”

With regard to the senior level of the organisation, Ronconi added: “A Council should be established above these levels on a ‘vertical’ basis to coordinate activities as part of an all-out war against subversion by communists and their allies. These represent the nightmare which looms over the modern world and prevents its natural development.”

Texts on the threat of communism were nothing new, but here was something that was qualitatively new — and it was not just a theoretical essay. The organisation outlined by Filippani Ronconi was already being set up and would shortly become operational.

In 1966 2,000 or so army officers received a leaflet through the post from the Nuclei di Difesa dello Stato. Its authors aimed to play on the servicemen’s pride: “Officers! The perilous state of Italian politics demands your decisive intervention. The task of eliminating the infection before it becomes deadly is one for the Armed Forces. There is no time to lose: delay and inertia represents cowardice. To suffer the vulgar rabble who would govern us would be tantamount to kowtowing to subversion and a betrayal of the State. Loyal servicemen of considerable prestige have already formed the Nuclei di Difesa dello Stato within the Armed Forces. You too should join the NDS. Either you join the victorious struggle against subversion or subversion will raise its gallows for you. In which case it will be the just deserts of traitors.”

The authors and distributors of this leaflet were Franco Freda and Giovanni Ventura, two of the main protagonists of the outrages.

Another individual of some note in this tale appeared on the scene at this time: Guido Lorenzon who was an officer on the establishment of the base in Aviano at the time and who was among those who received the leaflet. He mentioned it to his friend Ventura and — surprise, surprise — Ventura admitted that he was one of the authors of the document. He would eventually be convicted with Freda in 1987 of incitement to crime.

Along with the Freda and Ventura, someone else was working to set up the Nuclei di Difesa dello Stato network — which shadowed the better known, but more dangerous ‘stay-behind’ secret army organisation, Gladio.

After a refresher course with the Third Army Corps in Milan in the autumn and winter of 1966-1967, Major (now colonel) Amos Spiazzi, in charge of the army’s I (Intelligence) Bureau in Verona was tasked by his superiors “individually and by word of mouth” to shadow Gladio’s structure in his home city. As Spiazza told Guido Salvini on 2 June 1994: “I was also informed that, on a region by region basis and province by province, personnel with similar characteristics needed to be recruited, in units as water-tight as possible and trained in three man teams […] using the services of instructors from the local units […] These Nuclei adopted the designation of Legions […]. In this way I set up the Fifth Legion with 50 hand-picked people “.

Spiazza, who had been front-page news in 1974 over his involvement with the Rosa dei Venti subversive network, continued: “At meetings […] there was pressure for ever closer collaboration with the Corps, with existing political associations such as the Friends of the Armed Forces, the Pollio Institute, Combattentismo attivo, in order to bind our efforts into active endeavour to defend, support and make propaganda on behalf of the Armed Forces and the values for which they stand.”

Spiazzi’s involvement was not limited to training: he organised conferences and debates, contributed to the journal of General Francesco Nardella‘s Movimento di Opinione Publica (Nardello was a member of Licio Gelli’s P2) and was in touch with Adamo Degli Occhi, a Milan lawyer who led the demonstrations of the alleged Maggioranza Silenziosa (Silent Majority), and with Junio Valerio Borghese’s National Front (Borghese had been commander of the Decima MAS and had defected to the Salò Republic in 1943).

He stated: “Every single thing I did outside the service within the context of these activities was known to my I Bureau superiors.”

From the Veneto region to Lombardy, and, more precisely, to the Valtellina, Carlo Fumagalli was a mythic figure as far as his men were concerned. As a commander during the resistance, he had headed a non-aligned unit, I Gufi, made up of “white” partisans. His group had worked closely with the American wartime clandestine service, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS, later the CIA), for which he received the Bronze Star at the end of the war. Fumagelli maintained his links with the American intelligence services and at the end of the 1960s he was ready to help influence the Italian political system towards a presidential structure with an even more emphatically pro-NATO stance.

Fumagalli had set up the Movimento di Azione Rivoluzionaria (MAR) and to provide cover for its illegal activities, he ran a garage, which specialised in off-the-road vehicles and associated activities. He wholeheartedly adopted the strategy of provocation through attacks intended to be blamed on the left, but the coup d’état for which he yearned had none of the pro-Nazi connotations of his “allies”. Not that this stopped him from mounting spectacular operations.

A fire started in the Pirelli-Bicocca tarpaulin depot in the Viale Sarca took ten hours to burn out. The damage was estimated at a thousand million lire at the time. During the fire a 30-year-old worker, Gianfranco Carminati, lost his life. Years later Gaetano Orlando, the man regarded as the MAR’s ideologue admitted: “The MAR group’s plan was that the attack should be put down to the Red Brigades which were on the rise at the time”.

“I remember the Pirelli attacks at the beginning of 1971 and can confirm that our organisation had nothing to do with big fire at the Pirelli-Bicocca tarpaulin depot” was the claim made on 23 July 1991 by Roberto Franceschini, the then leader of the Red Brigades in Milan, who has since severed all ties with terrorism.

Exactly one month earlier, on 7 December 1970, a number of armed columns led by Prince Borghese from the Fronte Nazionale entered Rome. Among the main financial backers of the operation were Remo Orlandi, a Rome builder and Borghese’s right hand man, and Attilio Lercari, from Genoa, the administrator with Piaggio. The objective was to seize the main political headquarters, the RAI TV station and the airport, while Stefano Delle Chiaie’s men (Avanguardia Nazionale [AN] — personnel) were to seize control of the operations centre at the Interior Ministry. The ministry would be handed over to the carabinieri while the AN people rounded up political opponents for internment on the Aeolian Islands. Ships provided by Genoa shipping magnate Cameli were on stand-by to transport them.

It was a classic coup d’état. But something went awry, or somebody backed out. After a frantic round of phone calls the would-be coup-makers pulled out of Rome. Roberto Palotto and Saverio Ghiacci who, with other Avanguardia Nazionale militants, had succeeded in getting inside the Interior Ministry (with the help of Salvatore Drago, the duty physician at the ministry and P2 member), had to evacuate the building at speed. But the coup attempt was not confined to the capital.

“The Major told us to wear civilian clothes and maintain a state of readiness”, remembered Enzo Ferro one of Spiazza’s junior officers doing his army service in the Montorio barracks in Verona in December 1970. “We were due to be brought to the Porta Bra district in Verona, to the premises of the Associazione mutilati e invalidi di guerra, where the Movimento di Opinione Pubblica bulletin was published. […] We were told that we were to step in and could not back out and that, on reaching the muster-point, we would be armed and taken into the area where we would be providing back up for the coup d’état. Every civilian and military cell would be involved. But Major Spiazzi told us in person around 1.30am that orders standing-down the operation had been received from Milan.”

“In Venice too […] on the night of 7 December, arrangements had been made for people to muster at specific points. Muster they did, but shortly after that the stand-down orders arrived, much to the disappointment of all those present […] The rendezvous point was the Naval Dockyard — that is the area outside the Naval Command. In connection with these initiatives I reported regularly to Verona (to the FTASE — NATO Intelligence Service), which I then briefed on various developments” explained Carlo Digilio, who was linked with the Venice Ordine Nuovo group and had been a CIA asset since 1967. The agent to whom Digilio reported was Sergio Minetto, head of the CIA network in the Triveneto area. Minetto, of course, denied his part in the affair. The FTASE to which Digilio alludes was the general command of the Atlantic Alliance in Southern Europe.

“In Reggio Calabria,” recalled Carmine Dominici, a member of Avanguardia Nazionale — led in that city by the Marchese Felice Genoese Zerbi — “we were all mobilised and ready to do our bit. Zerbi said he had been given carabinieri uniforms and that we would be going on patrol with them, also in connection with the drive to arrest political opponents named on certain lists which had been drawn up. We remained in a state of readiness almost until 2.00 am. but then we were all told to go home.”

Other evidence, again collected by Judge Salvini, revealed that in many places around Italy, servicemen, civilians and carabinieri were on stand-by to act in support of the coup d’état in Rome.

The man who called a halt to the operation was in fact its mastermind, Licio Gelli who was also to have supervised the kidnapping of Giuseppe Saragat, Italy’s president. Gelli was later to exploit the involvement in the coup of a number of high-ranking officers for his own blackmail purposes and long-term intrigues.

[NB – Borghese’s plot was closely modelled on the 1964 Plan Solo coup — which was to conclude with the assasination of prime minister Aldo Moro — planned by carabinieri general Giovanni De Lorenzo]

But the verdicts handed down in November 1978, November 1984 and finally by the Court of Cassation in March 1986 cleared the conspirators of all charges. As for Gelli and the conspiratorial activity of the members of lodge P2 over many years, a definitive ruling from the Court of Cassation on 21 November 1996 found that Gelli should be sentenced to — but not serve— 8 years, solely for the offence of procuring sensitive intelligence, thereby closing the case begun in 1981, when the Guardia di Finanza discovered a list of 962 names of P2 lodge members in Gelli’s home, the Villa Wanda, in Castiglion Fibocchi.

That investigation had been taken from Milan magistrates Gherardo Colombo and Giuliano Turone and transferred to Rome. The prosecutors in the capital had done their duty and stymied the investigation.

The Night of the Republic