THE PIAZZA DUOMO was packed. The trade unions had supported this rally. Thousands of Milanese huddled in the cathedral square. The Duomo was overflowing with people. The archbishop of Milan, Cardinal Giovanni Colombo, officiated at the funerals of the 14 victims. Prime minister Mariano Rumor represented the State, while mayor Aldo Aniasi represented the city. Absent from the Piazza del Duomo on the morning of 15 December was a figure of some importance in this affair — not only important but crucial: the unwilling protagonist, Pietro Valpreda.

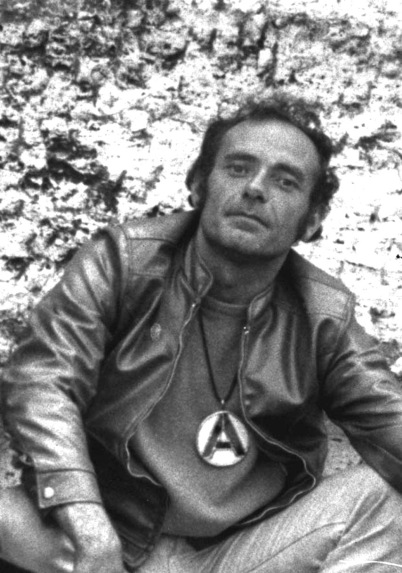

Valpreda was a 36 year old Milanese anarchist who, in his younger days, had lived in the Via Civitale in the San Siro district, a few hundred metres from the first marital home of Pinelli and his wife Licia Rognoni. Valpreda lived the typical life of a suburban kid. He had a couple of convictions: in 1956 he had been sentenced to four years in prison by the Milan court of assizes for armed robbery and a second conviction, for smuggling, dating from 1958.

He began taking an interest in political and social issues after his release and devoted himself to reading the works of anarchist thinkers: Mikhail Bakunin, Peter Kropotkin, Errico Malatesta. He also studied modern dance and toured with a few cabaret acts. He had also had the occasional television booking.

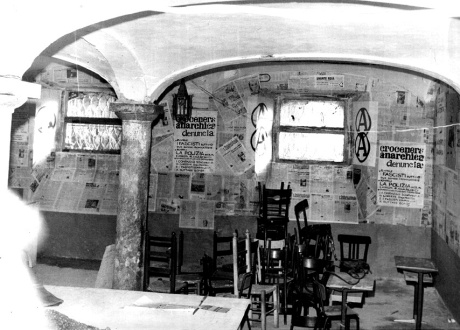

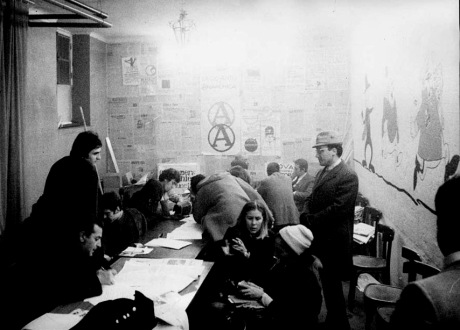

In the early 1960s poor circulation forced him to undergo an operation on his legs His involvement with the Milan groups was fitful, but when he was in Milan he usually sought out the anarchists from the Circolo Sacco e Vanzetti at 1, Viale Murillo near the Piazzale Brescia. From May 1968 onwards, he began calling in at the Circolo Ponte della Ghisolfa, the Milanese anarchists’ new premises.

Valpreda was of average height, agile, ever ready with a witticism spoken in a typical Milanese accent with its slightly rolled ‘r’. Early in 1969, he moved to Rome where he began to frequent the Circolo Bakunin, groups affiliated to the FAI (Italian Anarchist Federation). After falling out with them, he broke away, with Mario Merlino, Roberto Mander, Emilio Borghese, Roberto Gargamelli and Enrico Di Cola to set up the Circolo 22 Marzo at 22, Via del Governo Vecchio. By now his theatre work had dried up and he was to all intents unemployed, so he joined with Ivo Della Savia (who was replaced by Giorgio Spano when Della Savia left the country in mid-October) to open a retail workshop in the Via del Boschetto where he made liberty lamps, jewellery and necklaces. Among the materials he used were coloured glass settings. Curiously, one very similar to them turned up in the bag containing the bomb at the Banca Commerciale. Valpreda had also been in Milan from 7 to 12 December, having left Rome the previous evening to answer a summons from judge Antonio Amati.

At eight o’clock on 15 December, Valpreda, accompanied by his grandmother Olimpia Torri, went to the chambers of his lawyer Luigi Mariani at 39 Via San Barbara. He was due to report to Amati, the investigating magistrate handling inquiries into the 25 April bomb attacks at the Fair and at Milan’s Central Station. Amati considered himself an expert on anarchists and attentats. Shortly after the Piazza Fontana explosion, he ‘knew’ immediately that it had been a bomb and that that nobody but anarchists could have planted it — and said as much in a telephone call to the investigating officers at Milan police headquarters.

Valpreda made his way to the Palace of Justice with Mariani and Luca Boneschi, another of his lawyers. The two lawyers left him there, arranging to meet after the questioning. Valpreda left his grandmother to wait for him and knocked on the door of Amati’s chambers. This was at 10.35 am. In he went to be greeted by the judge with an exclamation of: “Ah, there you are!” “Yes, I was in Rome so couldn’t come any earlier. You know, I’m a dancer and actor and I have to move around for reasons of work”, Valpreda replied.

Judge Amati cut him off with a flurry of questions: “But who are you anarchists? What do you want? Why this great fondness of yours for blood?” This exchange (real or imagined?) took place in the judge’s chambers, but somebody got wind of it and it was to turn up in the columns of the following day’s Corriere della Sera.

It was Giorgio Zicari, a very particular brand of reporter. At the time, in 1969, he was a secret service informant, but he was not so much an inform-ant as an inform-ee, someone through whom the secret services funnelled news or — rather — confidential whispers.

It was then then minister of Defence, Giulio Andreotti, who lifted the veil on Zicari’s role. In an interview with journalist and erstwhile secretary of PCI leader Palmiro Togliatti Massimo Caprara, published in the weekly Il Mondo on 20 June 1974, Andreotti admitted that Zicari was ‘an unpaid informant for the SID’ and that later he ‘shifted across to the Confidential Affairs Bureau of Public Security.’ (Ufficio Affari Riservati)

Zicari had been in the right place at the right time — as he would be on many subsequent occasions: he had apparently exclusive access to confidential information from police headquarters and the courts.

From his privileged vantage-point, Zicari watched as Valpreda left after being interrogated by Amati at 11.30 am. He watched as Valpreda was led away by two police officers who held him, forcibly, under the arms and took him to a side-room of the court where he was handcuffed and taken to police headquarters.

Valpreda’s grandmother, Olimpia could not understand what was going on. She called out to ‘my Pietro’ but the policemen marched him off to the Via Fatebenefratelli where, after a brief interrogation, he was left on his own in a room. He was then taken to Rome’s police headquarters in the Via San Vitale there where Umberto Improta, a Special Branch inspector (who later went on to become police chief of Milan) was waiting for him, Alfonso Noce, another police officer, police brigadieri Remo Marcelli and Vincenzo Santilli who took the first official statement at 3.30 am. on 16 December.

Prior to that, however, between 2.00 and 3.00 am., Valpreda had gone with the officers to a field adjacent to the Via Tiburtina to search for an explosives dump, but nothing was found.

Valpreda allegedly made the following statement: “As we were going down the Via Tiburtina, before leaving for Rome that last time, we were just about level with the Siderurgia Romana foundry and the Decama works, about two or three hundred metres from the Silver cinema […] when Ivo Della Savia, pointed out a clump of bushes and said : ‘ I have some gear stashed there, not too far from the street at the foot of a shrub that is not too tall’” And he added: “He was not specific as to what he was talking about, but we took the reference to ‘gear’ to mean explosives, detonators and fuses .”

Why did Valpreda make that admission? Simple. Mario Merlino had been the first of the 22 March group to be questioned by the Rome police, but as a witness not as a suspect.

At 1.45 pm. on 13 December Merlino made a statement to this effect: “Concerning the bombings […] I am in a position to state that my friends Emilio Borghese, Roberto Mander and Giorgio Spano spoke to me on separate occasions of the existence in Rome of their cache of weapons and explosives […] Nearly six weeks ago, at the premises of the Circolo Bakunin in the Via Baccina Spano, talked about attacks in general and told me he had knowledge of facts and details concerning the attacks mounted in Rome …”

When questioned, again as a witness, Merlino (who would later be indicted with Valpreda and the other anarchists from the 22 March Group) said other things that were to condemn his comrades.

He declared: “On 28 November, on the occasion of the national ironworkers’ rally in the Piazza Santa Maria Maggiore, at about 11.00 am., while the students who later joined the workers’ march were assembling, Roberto Mander told me he needed explosives as the political situation was developing so quickly and it was time to act. Furthermore, on the 10th or 11th of this month, at around 8,00 pm., in the Via Cavour, after I had mentioned a few things that I had been told by Emilio Borghese, Roberto told me that they did indeed have a dump on the Via Casilina.” A moveable dump, then, that had moved from the Via Tiburtina to the Via Casilina. Having more to do with bragadaccio than with dynamiting activity, perhaps, Merlino continued: “One or two evenings prior to the encounter with Mander […] at the premises of the anarchist Circolo 22 Marzo, Emilio Borghese told me he had a cache of explosives, detonators and arms in the Via Casilina. He specifically stated that he had […] a substantial amount of detonators and a smaller quantity of explosives […] I remember he went on to say that he had gone to the dump several days previously in the company of Roberto Mander and Pietro Valpreda, in the latter’s car, and had removed or left […] a quantity of explosives.”

Here is the first contradiction. If Mander had ready access to the famous dump, why did he need explosives? And why had he turned to Mario Merlino? It is a mystery, one that Mander himself, a 17 year old high-school student, the son of an orchestra leader, tried to dispel in a 15 December interview with the police: “On 28 November, the day of the foundry workers’ strike, I mentioned to Merlino the possibility of bombs being set off to create incidents. That is to say, we discussed if it might help the foundry workers in the event of clashes with the police.

The following week Merlino asked me if it was true that I and Valpreda had an explosives dump in the Via Casilina. I asked Merlino to check where these rumours originated. On that occasion I asked him if there was any chance of his getting hold of explosives for the purposes of carrying out some sort of symbolic action. Over the next few days I put the same request about explosives to Borghese who had told me he did not have any to hand.”

Mander then stated: “I ought to stipulate that when I visited the Via Tiburtina with Ivo Della Savia, where I had been told there was a dump of materials — fuses and detonators I seem to recall — there were no explosives.”

In a later statement, Mander added: “I believe Valpreda is more an expert in the handling of explosives than I am. For years he has been active in anarchist groups — and he was also implicated in the Milan Fair attacks. I believe he was involved in other attacks as well.”

The Circolo 22 Marzo members then began pointing the finger at each other. Merlino insisted: “Let me add that today at police headquarters, after I said that the detective had queried the existence of an anarchist explosives cache in the Via Casilina, Mander replied: ‘They know about that then?’ […] Borghese also told me that he had access to other explosives but I don’t know where they were kept.”

Roberto Gargamelli, the 20 year old son of a Banca Nazionale del Lavoro official, refused to be sucked into this police-orchestrated game and at 5.00 am. on 15 December made the following statement:

“During meetings with Valpreda, whether singly or with other comrades, I never heard him speak of explosives. I mean that I never heard Valpreda, Mander or Borghese mention acquiring explosives, nor did I ever hear talk of there being an explosives dump or arsenal in the Via Casilina or the Via Tiburtina where Mander or Borghese supposedly had a cache of such material.”

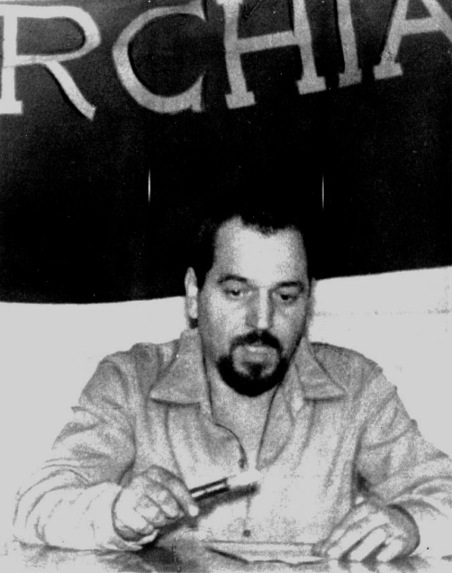

But who was this Merlino character who was so determined to throw suspicion on to his comrades? He was a 25 year-old philosophy graduate, son of a Vatican employee (employed by the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith department). In 1962, at the age of 18, Merlino had been active in far right groups, especially Stefano Delle Chiaie’s Avanguardia Nazionale. He also had connections with Pino Rauti, the Ordine Nuovo founder who now leads the Movimento Sociale Fiamma Tricolore and with the MSI deputy Giulio Caradonna.

Caradonna, a prominent hard-line Italian fascist, led the 200-odd Giovane Italia (Young Italy) activists (Mario Merlino among them) in the 17 March 1968 fighting with the leftist students squatting in the Faculty of Letters at La Sapienza university in Rome.

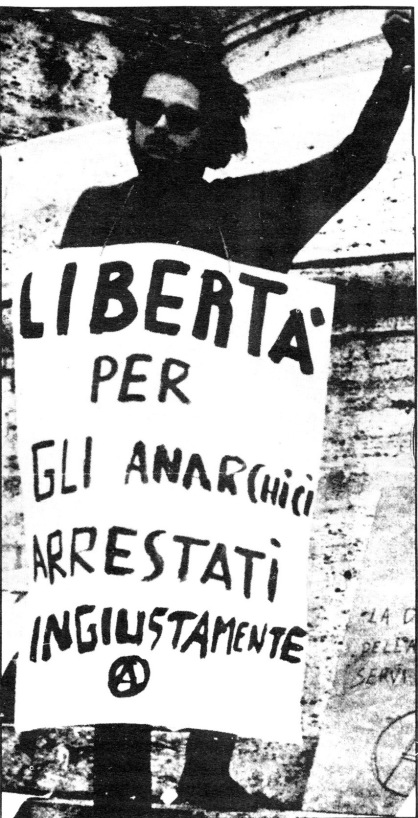

In April that year Merlino had gone to Greece on a trip sponsored by the ESESI, the league of Greek fascist students in Italy — organised by Pino Rauti and Stefano Delle Chiaie. On his return, Merlino underwent a political conversion. He adopted the dress of the more radical left, grew a beard and moustache and began frequenting groups from the extra-parliamentary left. He launched the Circolo XXII Marzo, which led to the later Circolo 22 Marzo. He distributed leaflets singing the praises of the student revolt in Paris and carried a black flag emblazoned “XXII MARZO” at a demonstration outside the French embassy. By September 1969 he was a member of the Circolo Bakunin in the Via Baccina, where he made no secret of his fascist past, claiming he was an ex-camerata — as well as being an anarchist sympathiser. Within the Circolo Bakunin he associated with those militants who complained the most about its political line and by the end of October he joined with these to launch the Circolo 22 Marzo.

Merlino remains to this day a figure who defies description. Even after they had been arrested and jailed, Valpreda persisted in defending Merlino, arguing that even a fascist had a right to a change of mind and that the climate created by contestation had shattered many of the certainties of members of the far right.

The fact remains that links with the camerati (fascist network) and above all with Delle Chiaie survived his alleged conversion to anarchism. Thus, when he saw the police had him cornered — when his status switched from witness-informant to suspect-under-investigation — Merlino had only one person to turn to for an alibi for the afternoon of 12 December — Stefano Delle Chiaie, a man who would eventually be indicted for perjury. So much so that in January 1981, in an interview with the weekly L’Europeo, Merlino acknowledged his debt of gratitude to Delle Chiaie:

“He told the truth and even now, 11 years on, he continues to do so […] But that is not the only reason why I hold him in such high regard. In relation to the Bologna bombing, for example, he was the only one with courage enough to say certain things, to own up to his own responsibilities in regard to terrorism, be it red or black. Unlike certain people, like Rauti or Almirante, who engaged in the splitting of hairs, if not trotting along to police headquarters to hand in the membership lists of Terza Posizione.”

Whereas Valpreda showed solidarity with Merlino, he had misgivings about someone that he could not quite identify:

“There was a spy in our ranks […] The police knew our every move and whatever was said at the Circolo”, Valpreda wrote to his lawyer Boneschi on 27 November 1969.

His intuition was correct, but Valpreda did not yet know the identity of the spy who so diligently briefed the police on everything being done by the young anarchists from the ‘22 Marzo’.

Who was it? It was “comrade Andrea”. That was the name by which the anarchists from the Via Governo Vecchio knew him. His real name was Salvatore Ippolito, he was a public security agent given the task of infiltrating the Roman anarchists. Two people — Merlino and Ippolito — therefore were monitoring the tiny group. The former reporting to Delle Chiaie, the latter to his superior officer at police headquarters, commissario Domenico Spinella.

But the ace up the police’s sleeve was neither of them. It was “super-witness” Cornelio Rolandi, a Milan taxi-driver. Rolandi approached the carabinieri and then the police to make a statement. He claimed to have driven the man who planted the bomb in the Piazza Fontana.

Rolandi was taken to Rome, where he arrived at 5.00 pm. on 16 December, and an identification parade was hastily organised. Valpreda was lined up with four policemen (Vincenzo Graziano, Marcello Pucci, Antonino Serrao and Giuseppe Rizzitello). Also present were: Rome prosecutor Vittorio Occorsio (who was to perish on 10 July 1976 at the hands of an Ordine Nuovo commando led by Pierluigi Concutelli and Gianfranco Ferro) and Guido Calvi, Valpreda’s defence counsel.

Prior to the ID parade, Rolandi declared: “The man I am speaking about is 1.70 to 1.75 metres tall, aged about 40, normal build, dark hair, dark eyes, without moustache or beard. I have been shown a photograph by the carabinieri in Milan that I was told must be the person I should recognise. I was also shown photographs of other people. I have never had this experience before.” Rolandi then picked out Valpreda. Valpreda asked him to look more closely, but Rolandi responded with: “That’s him. And if that isn’t him, then he’s not here.”

It was on the basis of this evidence — the absurdity of which would later be exposed — a monster was created. The press could now crow success: “The terror machine has been cracked.”