On 5 December 1969 the Piazza del Duomo was packed with left-wingers, rather than the expected fascists

Mariano Rumor wasted no time. The day after the bombings of 12 December 1969, the prime minister called a meeting of the secretaries of the Christian Democrats, the Socialist Party, the Unified Socialist Party (the name used by the social democrats after the socialist split on 2 July 1969) and Republican Party. His aim was to rebuild a four-party coalition cabinet.

It was to take them over three months to come up with a new government line-up. The overall impression was that although the socio-political situation might be dramatic, in the palaces of Rome they were still using the same old alchemy in the allocation of ministerial portfolios likely to assuage the various political camps.

Mauro Ferri and Mario Tanassi, the two leaders of the new social democratic party, were behind a strong government that — riding the wave of emotion triggered by the bombs — sought to impose an authoritarian stamp on the country. They spoke for that “American party” (as it was known) which vehemently opposed Italy’s progressive drift leftwards.

Rumor’s real intention was to establish a centre government of Christian Democrats and the Unified Socialist Party that would crown, at policy level, the strategy that had led to the Piazza Fontana carnage. But the enormous turnout of trade unionists and left-wingers at the funerals in Milan forced him to think again.

The situation that had developed since 1968 was worrying to broad sections of the middle and entrepreneurial classes. First the student unrest and then the labour unrest had fuelled their paranoia about the “red menace”. The traditional unions had for many months been unsuccessful at keeping their members’ struggles within the parameters of the usual demands. So much so that on 3 July 1969 a general strike called to press for a rent freeze witnessed the FIAT workers in Turin’s Mirafiori plant chanting an ironic slogan that had a threatening ring as far as the ruling class was concerned: “What do we want? Everything!”

That slogan had immediately taken off. Soon it was being chanted with growing insistence on marches. And in fact 1969 recorded 300,000 hours lost to strikes as compared with the 116,000 average for the 1960s. Labour costs were on the rise, from 15.8 per cent (or 19.8 per cent in industry), increasing the wages component of the gross national product from 56.7 up to 59 per cent. A discernible shift in earnings was under way. A threat to the privileged classes of society and to those who only a few short years before had been the beneficiaries of the “economic miracle”.

A seemingly pre-revolutionary situation existed in the country. Even though the revolution for which most students and a segment of the workers yearned for was not merely a distant prospect, but a practical impossibility, but what did that matter? Many honestly believed it was just around the corner, and many more were afraid that that was the case.

Even though the advocates of the radical transformation of society were a tiny minority compared with the total population, the nation’s political axis was shifting to the left. Although harshly criticised by the extremist fringe, the Communist Party was preparing to expand into new areas. Caught on the hop by the student demonstrations at the start of 1968, the Communist Party leaders from the Via Botteghe Oscure quickly deployed to make up the lost ground, especially in the field of institutional politics — parliament. So much so that on 28 April 1969 the debate began on disarming the Italian police in an attempt to turn them into British “bobbies”. It only took the bombs in Milan on 25 April to consign that scheme to utopia.

The strategy of tension was under way. This phase involved a revamping and synthesis of what had already been devised in theory and put into practice since the mid-1960s by leaders of the far-right and important elements in the armed forces. Italian Nazis and fascists were eager to eradicate the “communist contagion” and in this they were aided, abetted, monitored and, ultimately, directed by the Italian and American secret services.

The CIA had been operating in Italy since the end of World War Two. In 1947 it had funded — through the AFL-CIO — the breakaway socialist party led by Giuseppe Saragat and helped by anti-Stalinist revolutionaries, the Iniziativa Socialista, led by Mario Zagari. Apart from the ideological motives that drove Saragat and Zagari, the CIA’s dollars successfully undermined the Popular Front and facilitated the victory of the Christian Democrats on 18 April 1948 when they took 48.5 per cent of the votes and won an absolute majority in the Chamber of Deputies.

That victory had almost been written off. On 20 March 1948, George Marshall, the US Secretary of State, had warned Italians that in the event of a communist victory all US aid to Italy would dry up. In 1969 the CIA found its activities facilitated — the Italian president, Saragat, was a man who owed them a favour.

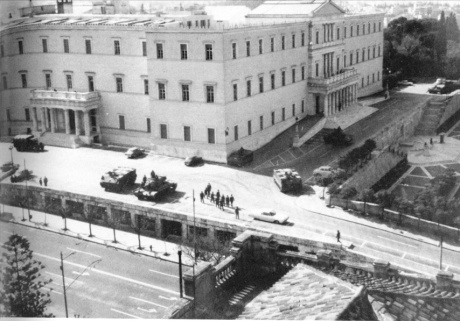

The CIA had one great foe — communism, just as the KGB used every method available to it to combat the West. But whereas in the Third World the two agencies fought on almost equal terms — with the KGB having the edge — in the west the CIA brooked no interference. So much so that in 1967 it came up with a brilliant resolution to the Greek crisis by installing its own man, George Papadopoulos in power by means of a coup d’état. From this point on the “coup-makers” held the upper hand in the Agency in Europe — and would continue to do so right up until the mid-1970s.

After Greece it was Italy’s turn and within the US-dependent SID the coup-maker faction was in the ascendant. From 1966 — the year he took office — Admiral Eugenio Henke led the SID and D Bureau was headed by Federico Gasca Queirazza, one of those who had been briefed in 1966 by agent Guido Giannettini on what the Venetian Nazis Franco Freda, Giovanni Ventura and Delfo Zorzi were planning.

Gasca Queirazza passed this information on to his superior, Henke, who in turn forwarded the information to Interior Minister Franco Restivo. Did Restivo pass on this information to his party colleague and prime minister, Mariano Rumor? No? That takes some swallowing, if only because the repeated unbelievable attacks of amnesia suffered by Rumor during the first trial in Catanzaro provoked such hilarity, in spite of the dramatic setting.

When Vito Miceli took over from Henke in 1970, the coup-maker faction was no longer simply diligently coordinating the attacks mounted by the far-right, it had taken the initiative as a direct organiser and Junio Valerio ’s coup attempt was part and parcel of this new dynamic. Miceli was also to stand trial for this later, but, as ever, nothing came of it.

When they struck on the night of 7 December 1970’s men were not nostalgic old codgers. They had substantial cover and assistance. Miceli briefed Defence Minister Tanassi on what was happening, as did the chief of staff, Enzo Marchesi. In fact, Restivo knew everything even before the plotters held part of his ministry for a few hours. But when questioned in parliament on 18 March 1971, after the news had broken, Restivo denied everything. Naturally.

The history of the coup in Italy remains unfinished business, as is the case of Piazza Fontana. History repeated itself in April 1973 with the Rosa dei Venti conspiracy, which involved even greater heavyweights who were much better prepared than Borghese had been — officers such as Colonel Amos Spiazzi (who had been around the block earlier, on 7 December 1970).

The man who oversaw this proliferation of attacks and coup preparations was a leading engineer by the name of Hung Fendwich whose office was based in Rome’s Via Tiburtina. But it was not located in the sort of secret lair that one might imagine; it was in the offices of the Selenia Company, part of the STET-IRI group, for which he worked.

Fendwich was the typical eminence grise who studied and refined plans, drew up analyses of the socioeconomic and political situation, but left the operational work — the “dirty work” — to men of more modest rank, men such as Captain David Carrett attached to the FTASE base (NATO command in Verona from 1969 to 1974), or his successor (up until 1978), Captain Theodore Richard based in Vicenza.

Sergio Minetto, one of the CIA’s top Italian informants, led these men. Minetto was the man to whom Carlo Digilio, their plant inside the Ordine Nuovo group in Venice, would have been reporting. As an operator it was he who prepared the explosives and trained Delfo Zorzi and Giovanni Ventura in the group’s powder magazine — an isolated house in the Paese district near Treviso.

The bomb attacks that erupted in Italy between 1969 and the mid-1970s (although they continued after that date) were regarded as overtures to a coup d’état. Indeed, although the coup never happened, it was always in the air and indeed had a precise function. It sent out a clear and menacing message to the opposition — i.e. the Communist Party.

But it was no coincidence that following the coup in Chile in September 1973 — which brought the number of military regimes around the globe to 47 — PCI secretary Enrico Berlinguer floated the idea (from the columns of the review Rinascita) of an “historic compromise” — i.e. for a government agreement between the Christian Democrats, the Italian Communist Party and the Italian Socialist Party. But it was to take another 23 years before the Democratic Left Party, the PCI’s heir, entered the government as part of a centre-left coalition.

The bombings crystallised the institutional political situation and in response the left presented the prospect of armed struggle. The ongoing outrages and the threat of a coup, among other things, drove many extra-parliamentary militants underground, including people such as the publisher Giangiacomo Feltrinelli.

All this gave rise to a vicious circle, which, to some extent, served as an a posteriori excuse for the theory of “opposing extremisms’. The only hope was to trust whoever was in power at the time — that is, the men who were rubber-stamping and providing the cover for what the Interior Ministry’s Bureau of Confidential Affairs and the SID were doing under instruction from the CIA.

From the ministers came the directives and the secret services carried them out — and added more than a little initiative in the process. It was no coincidence in 1974, when SID officers brought Defence Minister Giulio Andreotti (in the fifth Rumor government) the recordings made by Captain Antonio Labruna with industrialist Remo Orlandini, a man who had been caught up in the coup attempt. Andreotti’s advice was that they “do a bit of pruning”. Translation? Purge the tapes of the most important names, which is to say the names of high-ranking military personnel implicated in the failed coup attempt.

This behaviour was similar to that of his predecessor, Mario Tanassi (defence minister with the fourth Rumor government). In the summer of 1974 Judge Giovanni Tamburino asked the SID for information about the pro-coup activities of General Ugo Ricci whom he considered one of the men behind the Rosa dei Venti. The SID, who knew all about Ricci’s activities, reported that the general was a man of unshakable democratic beliefs. But before forwarding that report the SID chief forwarded the judge’s request to Tanassi who returned it with the annotation: “Always say as little as possible.”

The practice of saying nothing or telling lies continued through the years. On 13 October 1985 the weekly Panorama published extracts from a document by Bettino Craxi, the prime minister, inviting the men of the secret services “to abide by a policy of noncooperation” with the magistrates questioning him.

Craxi never denied the veracity of that report. How could he? But he did bring pressures to bear on the judges to ignore it. So the politicians knew all about the secret service plots — and were often the prime movers behind it. They knew that the fascists were being used to further the strategy of tension and they were either jointly responsible for this or direct promoters of it, like Restivo.

So there was raison d’état behind the 12 December 1969 bombs — a matter of opting for terrorism as a means of holding on to power.

“12 December 1969 signalled a watershed in the history of the republic, in the history of the left, in the history of movements […] because in effect on that date, along with 16 ordinary individuals there perished a significant portion of the first republic — a substantial portion of the machinery of state consciously plumped for illegality. It set itself up as a criminal power while continuing to man essential institutions and was permitted to do so (the ‘State servants’, policemen, judges, secret agents, politicians, secretaries, ministers, pen-pushers and henchmen who cooperated in the implementation of this crime and its cover-up by the laying of false trails, obstruction and ensuring the crime remained unpunished are numbered in the thousands). Since then, Italy has ceased to represent a constitutional democracy in the fullest sense”, wrote the political scientist Marco Revelli in his book Le due destre.

That political analysis is borne out and documented in the investigation carried out by Judge Guido Salvini: ”The protection afforded members of the Venice cell […] was absolutely vital, insofar as the caving-in of even one of the accused would have led the investigators, level after level, right to the highest powers who had made the operation on 12 December feasible, and the repercussions from that might well have proved incompatible with the maintenance of the country’s political status quo.”

Such widespread collusion also raises doubts. How much did the main opposition party — the Italian Communist Party, now the Democratic Left Party — know about the Piazza Fontana massacre? A lot, to be sure. But how much? And to what extent did the fear of bombs and coup d’états taint the PCI’s positions? To what extent was it induced by such fear to propose its historic compromise and then embrace coexistence? The answer to that can be found only in the archives in the Via Botteghe Oscure, which are as impenetrable as the Vatican’s.

But we can offer one answer, an answer which — given the guilt that lies at the highest levels — can only be that the massacre of Piazza Fontana was a State massacre. And the State was, moreover, the mother of all the massacres.