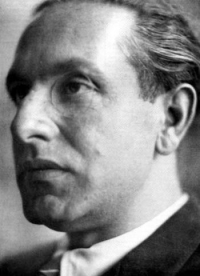

Francesco Restivo (1911-1976): Christian Democrat MP, President of the Regional Council of Sicily (1949-1955), and Minister of the Interior (1968 1972)

Two of the protagonists in our tale, Ordine Nuovo and Avanguardia Nazionale, were important and leading players. Why? According to the most recent evidence it was members of these organisations that carried out the outrages in Milan and Rome on 12 December 1969. But they were not merely the operatives of terror. The relationship between the executors and the masterminds was more complicated than that. It was not a simple case of “Take this bomb and go and blow the thing to kingdom come”. There was a web of complicities, promptings, assistance and mutual blackmail that added up to some of the most poisonous pages in Italian history. A history that witnessed the Interior Ministry itself, in the shape of the man in charge at the ministry, Franco Restivo and many of his successors, especially Federico Umberto D’Amato, head of the Confidential Affairs Bureau (disbanded in 1978) as puppet-masters of the strategy of tension.

The bottom dropped out D’Amato’s world (who died on 1 August 1996) when, at the end of that year, 150,000 or so uncatalogued files (from which some of the most compromising documents may well have been removed) were discovered in a villa in the Via Appia on the outskirts of Rome — and not just documents either. There was, for example, the dial of the timer used in the 9 August 1969 bombing of the Pescara-Rome train (the one carried out by Franco Freda himself).

This documentation, uncovered on 4 October 1996, after D’Amato’s demise, by Aldo Giannuli, an expert appointed by Judge Salvini, added up to an alternative record of the goings-on at the Viminale Palace. They contained information on many of the stories bound up with domestic espionage activity. It was a secret archive that had never been shredded, simply deposited higgledy-piggledy in a dump— perhaps for possible future use.

At this point we need to go back forty years or so when, in 1956, Giuseppe Rauti, known as Pino, began to display signs of intolerance towards the “petit bourgeois and legalitarian” policy of Arturo Michelini, the secretary of his party, the Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI). Michelini had been elected supreme leader of the Italian neofascists in 1954 and was regarded as too soft in the parliamentary confrontations between the Christian Democratic right and the “hard-liners” from Giorgio Almirante’s faction.

Rauti was one of the hardest of hard-liners. He broke away from the MSI to set up the Ordine Nuovo study centre with Clemente Graziani, Paolo Signorelli, Stefano Serpieri and Stefano Delle Chiaie. In the autumn of 1969, when Giorgio Almirante became secretary of the MSI, Rauti returned to the party and dissolved the study centre. This was only a formality as the Ordine Nuovo groups and organisation continued operating for several more years.

In 1958 Delle Chiaie began to cut loose from Rauti’s apron strings and in 1960 this led to his launching Avanguardia Nazionale. This latter organisation was formally disbanded in 1966 to allow many of its members to rejoin the MSI, but in 1968 Delle Chiaie formally refloated the never disbanded organisation.

Ordine Nuovo and Avanguardia Nazionale were substantially the same ideologically. Their main theoretical reference point was the philosopher Julius Evola, whom Rauti had known in the later 1940s. Their programmes were based on the struggle against communism and capitalism and in support of a corporatist State, following the model of the 28 August 1919 revolutionary nationalist programme of the Fasci di Combattimento established in the Piazza San Sepolcro in Milan on 23 March 1919. That programme had been refined (in its presentation at least) by the Salò Republic (the volunteers of which had included the then 17 year old Rauti). The fight was also directed against the parliamentary system and all forms of democracy, in order to bring about an aristocratic and organic State, borrowing the ideas of Nazi Germany. The ultimate goal was a New European Order.

In practice, both organisations shared Italian territory: Ordine Nuovo’s groups were located primarily in the North, whereas those of Avanguardia Nazionale were based mainly in Rome and the South.

By the spring of 1969 they began to operate jointly. The Venetian leadership of Ordine Nuovo met the Rome-based leaders of Avanguardia Nazionale on 18 April 1969 in Padua, in the home of Ivano Toniolo, one of Freda’s most loyal lieutenants. With the blessing of Carlo Maria Maggi, the boss of Ordine Nuovo in the Triveneto area and of the national leadership, Signorelli and Rauti. From then on the two organisations were to operate in concert with each other, at least in large-scale operations. On 25 April the bombs exploded in Milan (at the Fair and at Central Station).

An operational axis had been formed stretching from Venice through Padua to Milan, down to the capital and as far as Reggio Calabria. And the personnel? Venice was represented by Delfo Zorzi, Martino Siciliano, Giancarlo Vianello (who infiltrated Lotta Continua in 1970, fell in love with a member of that group and eventually parted company with his fascist colleagues), Paolo Molin and Piercarlo Montagner — with “technical” backup from Carlo Digilio.

In Padua, under Freda’s leadership, there were Giovanni Ventura, Massimiliano Fachini and Marco Pozzan. Giancarlo Rognoni was the acknowledged leader of the La Fenice group in Milan. In Rome, Delle Chiaie presided over Avanguardia Nazionale, while in Reggio Calabria its bulwark was the Marchese Felice Genoese Zerbi who could call on a sizable band of determined militants such as Carmine Dominici, Giuseppe Schirinzi and Aldo Pardo.

These were characters with chequered pasts. Freda and Ventura were eventually to be convicted of 17 attacks mounted between 15 April and 9 August 1969 (including the bombings in Milan on 25 April and the train bombings on 9 April). Rognoni was spared 23 years in prison by going on the run, primarily to Spain, and was in fact sentenced in his absence for an attack mounted by his lieutenant, Nico Azzi.

On 7 April 1973 a bomb exploded in a toilet on the Turin-Rome train, but the bomber, Azzi, however, did not get away unscathed. The device had exploded while he was handling it — or rather it went off between his legs. He was injured, arrested, tried and sentenced to 20 years. Two other La Fenice members — Mauro Marzorati and Francisco De Min — ended up in jail with him.

The attack, planned in the presence of Ordine Nuovo ideologue Paolo Signorelli, was intended to distract the Milan magistrates’ inquiries into the Piazza Fontana bombing — and as a focus for a maggioranza silenziosa (silent majority) demonstration planned for Milan on 12 April. Following the bombing someone was to have made a telephone call claiming responsibility on behalf of a leftwing organisation.

A strong character, tough, quick to use his fists, his face frequently marked by wounds, he was not impressed by the sight of blood and inflicted punishments personally on errant colleagues. But at the same time he was introverted and fascinated with both Buddhism and Evola’s ideas. This was how Siciliano described his leader, Zorzi. This was the man who would confess on at least two occasions that he had had a hand in the 12 December 1969 bombing in Milan.

On 31 December 1969, Zorzi, Siciliano and Vianello were celebrating New Year’s Eve with a visit to prostitutes in the Corso del Popolo in Mestre. “This was a cameratesca (comradely) practice linked to the fascist notion of virility”, Siciliano noted. They then went to Vianello’s home for a meal, a drink and to sing fascist songs. The conversation then turned to the bombings of a few days earlier.

Siciliano told Judge Salvini on 8 June 1996: “Zorzi reminded us that according to our greatest theorists even blood can serve as a trigger for a national revolution which, launched in Italy, could be the salvation of Europe by rescuing it from communism. He picked up on the line that had already been given out in Padua — that the common people, stricken and defenceless, would clamour for a strong State, especially since the strategy anticipated that such serious incidents would be laid at the door of the far left.”

According to Siciliano, Zorzi’s closing remarks were: “He gave us clearly to understand that the anarchists had had no hand or part in anything and that they had been used as scapegoats simply because of their history — that sort of charge levelled against them was believable — and that in reality the Milan and Rome attacks had even thought up and commissioned at the highest levels and actually carried out by the Triveneto Ordine Nuovo.”

In January 1996 Digilio told Judge Salvini what Zorzi told him in Mestre in 1973: “Listen, I was personally involved in the operation to plant the bomb at the Banca Nazionale dell’Agricoltura”. And, Digilio continued: “That was what he said, word for word and I remember it well, not least because of the seriousness of the words. Zorzi never mentioned those killed in the bombing but he did use the term ‘operation’ as if it had been a war-time operation.”

At this point Zorzi explained to Digilio: “I dealt with things personally and it was no easy undertaking. I had help from the son of a bank director.”

Zorzi moved to Japan after Judges Giancarlo Stizin Treviso, Pietro Calogero in Padua, Gerardo D’Ambrosio and Emilio Alessandrini in Milan began chasing up the fascist trail in connection with the Piazza Fontana outrage.

In Tokyo, where he now lives, having married a Japanese woman by whom he has had a daughter, Zorzi runs an import-export firm which has made him a (lire) multi-millionaire; so much so that in 1993 he was able to make Maurizio Gucci a loan of 30,000 million lire — a fortune some suspect he amassed thanks to the protection of the Yakuza, the Japanese Mafia, and of the Italian and US secret services. His Italian defence counsel is Gaetano Pecorella who denies his client had any involvement in the Piazza Fontana carnage. This is the same Pecorella who in the 1970s concentrated on defending leftwing activists before switching in the 1990s to a mixture of clients ranging from Zorzi to Ovidio Bompressi, the former Lotta Continua member sentenced to 22 years for the murder of Inspector Luigi Calabresi.

“I was in Naples attending the oriental university, in which I enrolled in 1968”, Zorzi stated apropos of 12 December 1969 in an interview carried by Il Giornale on 14 November 1995. That alibi has yet to be confirmed.

Another name, another fugitive. At the time he was being questioned by Judge Salvini, Digilio already had one ten year sentenced passed against him in his absence. In 1983 while a clerk at the Venice firing range, Digilio had been arrested for unlawful possession of ammunition. Although he had been freed after a few days, he realised other more serious charges could follow so he fled to an isolated house in Villa d’Adda in Bergamo province, moving on to Santo Domingo in 1985, on forged papers. He was arrested by Interpol in the autumn of 1992 and returned to Italy to serve his sentence: for resurrecting Ordine Nuovo, possession of detonators, dealing in weapons, possession of machinery for repairing and converting weapons and for forging documents.

Then we have the most famous fugitive of all: Delle Chiaie, known in Rome as “il caccola” (“the little man”) before he was re-dubbed “the black primrose”. During questioning at the Palace of Justice in Rome, he asked to use the toilet and vanished. That was on 9 July 1970.

Even though he was seen in the capital for several months thereafter the police never managed to recapture him.

After the failure of the coup, Delle Chiaie moved to Madrid where he could count on protection from the leading lights of Francoism, but in February 1977, by which time the Franco regime was no more, Delle Chiaie moved to the greater safety of Latin America.

On his return to Italy he refused to discuss this, even though Giorgio Pisanò, publisher of the fascist weekly Il Candido, sent him a clear message through his newspaper column. In an open letter published on 9 January 1975, Pisanò wrote: “Stay where you are and keep silent. If you return there are many things you need to explain: the arms dealing; the disappearance of funds entrusted to your care, your connections with Mario Merlino, or indeed your dealings with the Ministry of the Interior’s Confidential Affairs Bureau.” Delle Chiaie kept on the run — through Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay and Chile.

He adopted a new identity, calling himself Alfredo Di Stefano, but in 1987 he was arrested in Caracas and his 17 years as a fugitive from justice was brought to an end.

An international warrant had been issued for his arrest. On what charges? The Italicus bombing, theft, conspiracy to subvert, aiding and abetting the Piazza Fontana massacre, membership of an armed gang. He went on trial in October 1987 with Massimiliano Fachini before the Court of Assizes in Catanzaro (the last trials relating to the Piazza Fontana incident). On 20 February 1989, both men were cleared on all counts after 90 court sittings, a finding that was confirmed on appeal on 5 July 1991.