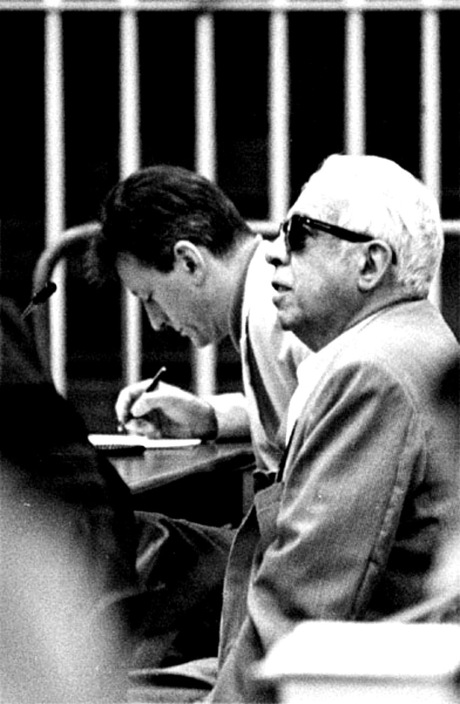

Pasquale Juliano tried but it blew up in his face.

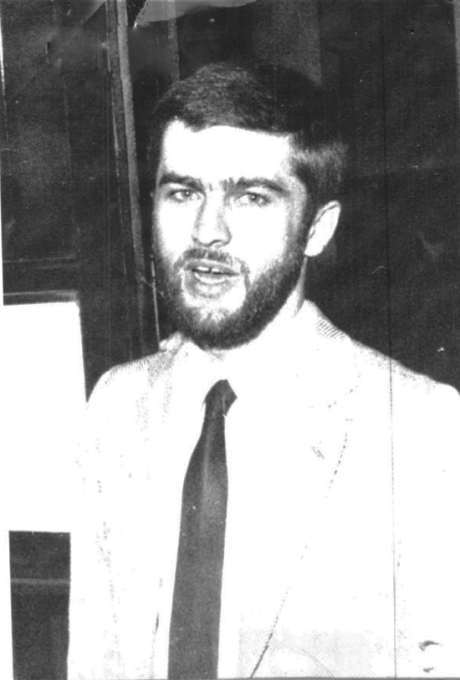

Franco Freda (one of the authors — with Ventura — of the Piazza Fontana bombing of 12 December 1969)

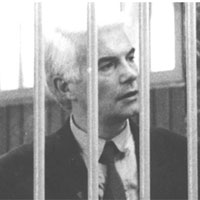

In the spring of 1969, the head of the Padua flying squad, Pasquale Juliano, developed an interest in the activities of a neo-Nazi group operating in the city. Some of his informants — Niccolò Pezzato and Francesco Tomasoni — had told him that the people responsible for the attacks on the homes of police chief Francesco Allitto Bonanno on 20 April 1968 and the office of university rector Enrico Opocher on 15 April 1969 were part of a group headed by Franco Freda.

Juliano organised a stakeout on the home of Massimiliano Fachini, convinced he was the quartermaster in charge of the group’s weapons and explosives. One June evening, thanks to his usual sources, Juliano surprised Giancarlo Patrese (another member of Freda’s group) at the house in possession of a bomb and a revolver. He ordered the arrest of Patrese, Fachini and Gustavo Bocchini, grandson of Arturo Bocchini, the one-time chief of police under the fascists. Juliano believed he had made a start on breaking up the bomb team, but instead he found himself caught up in an “affair” bigger than he was. Patrese confessed he had received the arms and explosives from none other than Juliano’s own informant, Pezzato, who had entered Fachini’s house with him.

This account of events was denied by the building’s concierge, Alberto Muraro, a one-time carabinieri. Patrese had entered on his own and left on his own, but his evidence was insufficient and Juliano was accused of having entrapped the three fascists.

The director of the confidential affairs bureau of the Interior Ministry, Elvio Catenacci then suddenly and unexpectedly intervened. Catenacci — the same official who conducted the investigation at police headquarters in Milan following Pinelli’s death — ordered Juliano’s immediate suspension from duty without pay and it was to be two years before he was reinstated and reassigned to Ruvo di Puglia, and it was not until 1979 that Juliano was finally cleared.

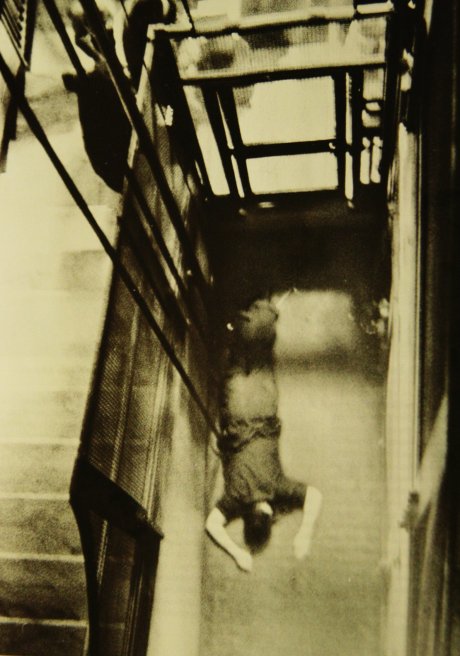

A campaign of dissuasion followed. Pezzato and Tomasoni, the informants, were jailed and placed in the same cell as Patrese, who persuaded them to retract. Meanwhile, on 13 September, the concierge Muraro was found dead at the foot of some stairs. Accidental death, investigators concluded, without so much as an autopsy, as would be normal in such cases. ‘One of these days you’ll drop by looking for me and I’ll be found with my head caved in in the cellar or in the lift shaft”, Muraro had confided to his friend Italo Zaninello shortly before his death.

Muraro had been due to present himself before the magistrate looking into the Juliano case two days later, on 15 September. The confidential affairs bureau had yet again intervened efficiently: Freda was not to be obstructed.

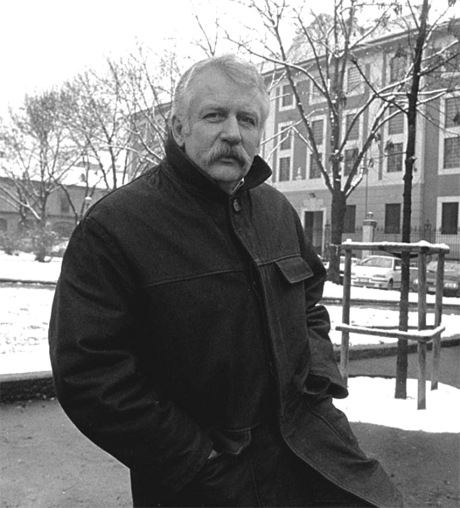

Notwithstanding the protection he enjoyed, Freda found someone else making inquiries about him — carabinieri maresciallo Alvise Munari.

The examining magistrate in Treviso, Giancarlo Stiz, had commissioned Munari —whose family had worked the land around Bassano del Grappa for generations — to investigate a lead resulting from a statement made by a teacher of French in Marrada, Guido Lorenzon, a member of the Christian Democratic Party.

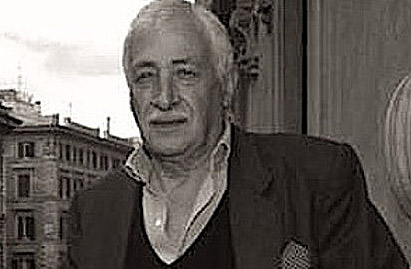

Vittorio Veneto, 15 December 1969. Lorenzon visited Albert Steccanella, a local lawyer who told him a long and convoluted story about a friend of his, Giovanni Ventura, a publisher and bookseller from Castelfranco Veneto. Ventura, Lorenzon said, had mentioned the 12 December bombings to him on the afternoon of 13 December, after returning from Milan or Rome and showed sufficient familiarity with the events and places involved as make an impression on Lorenzon.

Lawyer Steccanella sensed Lorenzon’s story might lead on to significant revelations, so he asked him to set it all down in a memorandum, which he did and delivered to him three days later. On 26 December, having realised the gravity of the facts provided by Lorenzon, the lawyer visited the Treviso prosecutor and related everything that his client had told him: that there was in the Veneto a subversive organisation which might just have been implicated in the massacre. Count Pietro Loredan backed this organisation from Volpato del Montello.

On 31 December Lorenzon called on the public prosecutor in Treviso, Pietro Calogero and told him about Ventura’s confidences. The publisher had planted a bomb which had failed to go off, in a public office in Milan, in May; he had funded the August train bombings; he knew the underpass at the Banca Nazionale del Lavoro where the bomb went off on 12 December like the back of his hand and could not understand how on earth the bomb in the Banca Commerciale in Milan had failed to explode. Also, in September, Ventura showed him a battery-operated timer. Furthermore, he was constructing a device for use against US president Richard Nixon during his forthcoming visit to Italy.

These were important revelations. On 12 February 1970, the examining magistrate in Rome, Ernesto Cudillo, was due to hear this witness from Venice, but he did not impress him. Even so, he could not completely ignore this encounter: on the afternoon of the following day, at the conclusion of the questioning of Pietro Valpreda, he asked the anarchist if he knew anyone by the name of Giovanni Ventura or Guido Lorenzon. “I don’t know anybody of that name. The only two Venturas I have ever met and known are both dancers”, was Valpreda’s response.

Lorenzon was so overcome with guilt at his betrayal of his friend Ventura that on 4 January 1970 he told him that he had approached the magistrates. Ventura and Freda then put the French teacher under pressure to change or retract his statement. A seesaw of statements and retractions followed, but anomalous retractions at that, as Lorenzon himself later confessed to the judges: “It occurred to me to retract something which I had never stated. I had mentioned things that I had heard, things which I had never actually seen, but I had never stated, say, that Ventura had gone to the Piazza Fontana and that Ventura had planted the bombs on the trains, but he still told me everything that I later recounted. In my retraction, however, I therefore retracted something that I had never said, secretly hoping that that statement might then be taken for what it was, to wit, false. It was only a way of buying time because at the time the magistrate was away and I had to face Ventura on a daily basis.”

Investigators finally kitted Lorenzon out with a tape-recorder to be used secretly in conversations with Ventura. The tapes were then forwarded to Rome, to Cudillo and his colleague Vittorio Occorsio, the prosecuting counsel who found nothing of interest in them. Occorsio, however, ventured the following statement: “Lorenzon’s charges are without foundation. In the lengthy taped conversations the only point of note is that Ventura offered no confidences of the sort and therefore spoke in terms that plainly show that he had nothing to do with the events. There is nothing to suggest that Ventura was, even marginally, an accomplice in the outrages of 12 December 1969.” Cudillo and Occorsio found Ventura “a decent guy” and Freda “a gentleman”. In short, they were two upstanding citizens who had been unfairly slandered by Lorenzon.

The Treviso magistrates did not share these opinions. When the tapes were returned to Stiz at the end of 1970, there was a change of tune. After listening carefully to the taped conversations, Stiz immediately sent for Lorenzon who confirmed everything to him. Stiz continued with his inquiries, carefully scrutinising the book Justice is Like A Tiller: It Goes Where It is Steered, written by Freda as an attack on Juliano’s investigation. He listened to other witnesses and on 13 April 1971 he indicted Freda, Ventura and Aldo Trinco for conspiracy to subvert the course of justice and, above all, for the bombings in Milan on 25 April and for the 9 August train bombings. But the trio’s defence lawyers petitioned for the case to be heard before the judges in Padua on grounds of territorial competence. The accused were released.

A further change of scene. On 5 November, during restructuring work at the home of Giancarlo Marchesin, a leading socialist in Castelfranco Veneto (Treviso), builders discovered a crate filled with weapons behind a wall. When questioned by Stiz, Marchesin admitted that the crate had been given to him by Franco Comacchio on behalf of Giovanni Ventura. The crate (which Comacchio had received from Ruggero Pan, an assistant in Ventura’s bookshop doing his military service at the time) had initially held explosives too, but Comacchio had hidden these in the countryside near Crespano.

On 7 November Comacchio went with some carabinieri from Treviso to collect the explosives. But without warning the carabinieri unexpectedly blew up the 35 sticks. But sticks of what? Judging by the characteristic smell of bitter almonds after the explosion, it must have been the by now famous gelignite.

Later statements by Carlo Digilio indicated that from 1967 the Ordine Nuovo groups in Padua and Venice had had a dump in the Paese area (near Treviso) where they had stored a large quantity of explosives and weapons in the use of which they were instructed by Digilio himself. It was later discovered that the few weapons shipped to Marchesin’s home were a tiny, tiny part of the two groups’ arsenal, which had been divided up after the Piazza Fontana massacre.

Questioned by magistrates, Pan began talking. Weapons and explosives had been passed to him by Ventura. Why? In 1968 Pan had worked in Ventura’s bookshop and on 10 March 1969 he had been hired, through Freda’s influence, as an attendant at the Configliaschi Institute for the Blind. The concierge there was Marco Pozzan, one of Freda’s most loyal followers. Freda had tried to draw the young Pozzan into his group and confided a number of things to him regarding the attacks being mounted in Padua and in other cities. All of these details wound up in an affidavit that Pan wrote in jail, heavily implicating Ventura and Freda, especially in the train bombings.

At this point in the investigations the name of Ordine Nuovo founder and Il Tempo reporter Pino Rauti came up — along with another journalist, Guido Giannettini (an important figure of whom more anon.) Rauti was also the author of the book Red Hands on the Armed Forces, published under the nom de plume Flavio Messalla.

Marco Pozzan implicated Rauti in subversive activity, along with Freda and Ventura. Pozzan insisted Rauti had taken part in a meeting of the group in Padua on 18 April, during which the bombings in Milan on 25 April were approved). Stiz and Calogero dispatched maresciallo Munari to Rome on 4 March 1972 to arrest Rauti on charges of massacre. On 22 March, Freda and Ventura were indicted in connection with the Piazza Fontana outrage.

Invocation of that crime obliged the Treviso magistrates to hand its case over to their Milan colleagues and from then on it was in the hands of examining magistrate Gerardo D’Ambrosio.

Rauti denied all charges and Pozzan retracted — and was promptly smuggled out of the country to Spain with the aid of the SID. Renato Angiolillo, Il Tempo’s publisher, and a number of editorial staff insisted that on the day in question, 18 April, Rauti had been at work in the editorial offices. So, one month later, on 24 April, D’Ambrosio freed Rauti on the grounds of insufficient evidence. The parliamentary elections were held on 7 May and Rauti was elected on the MSI ticket. The likelihood is that Pozzan implicated Rauti on Freda’s instructions in order to have someone in the frame someone who could mobilise the MSI on Rauti’s, and thereby also on Freda’s behalf.

But D’Ambrosio was more fortunate with Ventura who admitted involvement in the May 1969 attacks in Turin and those in July in Milan. More importantly, he implicated his friend Freda in the attacks. It was from Freda, the Padua lawyer, he had taken delivery of the bombs. Again, it had been Freda who had announced the August bombings before they happened. Point by point, everything in Lorenzon’s confession in 1969 was confirmed — almost four years after the event.

But something else emerged from the interrogations by the judges in Treviso and Milan, something considerably more serious for Ventura. It was proved he had definitely been in Rome on the afternoon of 12 December 1969. Ventura finally admitted this, but clung desperately to a weak alibi that was to soon be demolished — that he had gone to the capital because he had been informed the previous day his brother Luigi, a resident of a Catholic boarding school, had suffered a serious epileptic fit. The incident was true, but the date was false. According to Don Pietro Sartorio, the bursar of the home, Luigi Ventura had his attack at 12.30 p.m. on 14 December (on the Sunday rather than the Friday). Don Sartorio called a Red Cross ambulance and a physician who checked the boy over and said that no resuscitation was necessary — the fit having passed. The bursar informed the Ventura family of the fit and expressed his regret that he had not been advised of the boy’s state of health.

Ventura had been caught out — but there was more. He claimed that on the afternoon in question, after phoning the school and discovering Luigi was feeling better, he had visited a family friend, Diego Giannolla in his law chambers. He then went to the Lerici publishing house to meet his partner Rinaldo Tomba — alibis which both denied. In the end he claimed he had spent the evening of 12 December in the home of a friend, Antonio Massari who put him up for the night.

But that was not the only night Ventura had spent in Rome. According to the register of the Locarno hotel, he had stayed in Rome from 5 to 8 December as well as on the night of 10-11 December, only returning home on 13 December. Meeting up with Lorenzon that afternoon, he was excited about what had happened in Milan and Rome and initiated the loose talk that — after Lorenzon had reported it first to Steccanella and then to magistrates in Treviso — implicated Ventura and Freda in the bombings.