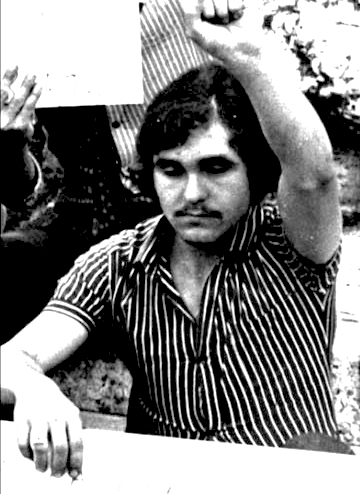

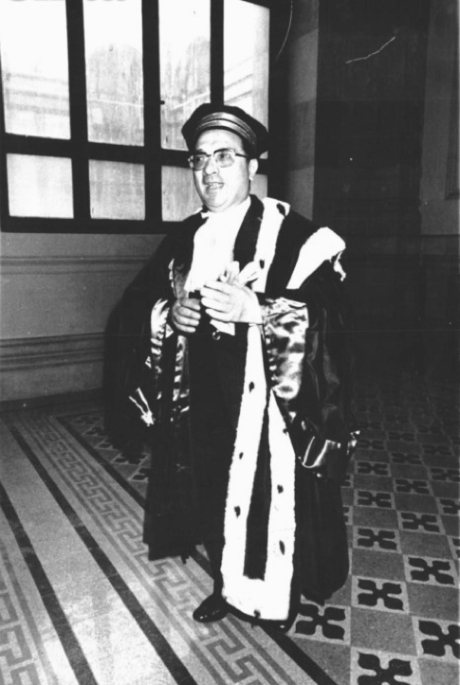

Rome, Feb 1972: Pietro Valpreda, Roberto Gargamelli and Emilio Bagnoli — and nine others (Piazza Fontana trial presided over by judge Orlando Falco)

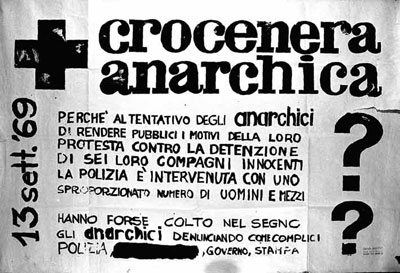

The proceedings had been under way for only a few days before everything ground to a halt. The scene was the Court of Assizes in Rome and the trial, which opened on 23 February 1972, was that of the anarchists from the Circolo 22 Marzo, of Pietro Valpreda’s relations and, in his absence, the Nazi-fascist Stefano Delle Chiaie for giving perjured evidence on Mario Merlino’s behalf.

But the judges, however, soon realised that the matter was not within their competence. Prompted by some of the anarchists’ defence lawyers — Francesco Piscopo, Giuliano Spazzali, Placido La Torre and Rocco Ventre — court president Orlando Falco chose to rid himself of what had become a hot potato of a trial. Even the public prosecutor Vittorio Occorsio tried to pin the shortcomings and partiality of the investigation on his colleague, examining magistrate Ernesto Cudillo.

It was as though he wanted it forgotten that he had launched the investigations. It was he who had arranged the identification by taxi-driver Cornelio Rolandi. Again, it was he who — in the indictment presented to the courts, as if to salvage the only piece of evidence on which he had built his indictment — had denied the glaringly obvious.

Occorsio wrote:

“What Rolandi claimed in the preliminary section of the identification document — ‘I was shown by the carabinieri in Milan a photograph that I was told must the person whom I should recognise’ — should be taken to mean that when Rolandi was shown Valpreda’s photograph at police headquarters, the taxi driver was asked to identify him — yes or no, of course — as the person he had carried in his taxi. Any inference in this connection regarding supposed and implicit solicitation of positive recognition is quite gratuitous.” And in order to hammer home this convoluted reasoning, he concluded: “Indeed if the word ‘should’ was used, the obligation implicit in that very term refers to the judicial burden of the act of identification rather to the results thereof.”

Faced with such untenable positions the Court in Rome switched everything to Milan on 6 March. The trial had returned, as judicial logic would have it, to the city where the massacre had occurred. But Milan prosecutor-general, Enrico De Peppo, was not having that. According to him, Milan could not offer the necessary neutrality in which to debate a matter of such delicacy. Furthermore — according to De Peppo — the city was virtually under the control of extra-parliamentary leftists eager to mount actions “designed to demonstrate — regardless of due process — the alleged innocence of Valpreda and the other co-accused.” Actions that might provoke a response from the far right. He applied to the Court of Cassation to have the case relocated again, and on 13 October the case was placed under the jurisdiction of the Catanzaro Court of Assizes.

But it did not begin immediately. It was not until 27 January 1975 that proceedings opened, proceedings that would find the anarchists — Pietro Valpreda, Emilio Bagnoli, Emilio, Roberto Gargamelli, Ivo Della Savia and Enrici Di Cola; Valpreda’s relations — Maddalena Valpreda, Ele Lovati, Rachele Torri and Olimpia Torri — in the dock beside the indescribable Mario Merlino, the Nazi-fascists: Franco Freda, Giovanni Ventura, Stefano Delle Chiaie, Marco Pozzan and Piero Loredan di Volpato del Montello; fascists working for the secret services: Guido Giannettini and Stefano Serpieri, and SID officers: Gianadelio Maletti, Antonio Labruna and Gaetano Tanzilli.

Why this motley crew? The Catanzaro court combined two trials that led to irreconcilable results — the investigation by Occorsio and Cudillo and the later investigation by Milanese magistrates Gerard D’Ambrosio and Emilio Alessandrini. The latter case also relied on inquiries conducted by magistrates in Treviso and Padua and elsewhere — inquiries that had brought to light the part played by the fascists and secret services in the bombing strategy.

The first verdict was returned on 23 February 1979, nearly ten years after the attacks. Three life sentences — for Freda, Ventura and Giannettini, for the massacre and outrages. But Giannettini was the only one in court: Freda was on the run in Costa Rica and Ventura in Argentina. Maletti was sentenced to four years for procuring perjured testimony and Labruna and Tanzilli each got two years. Valpreda and Gargamelli were cleared of massacre, on grounds of insufficient evidence and convicted on the count of criminal conspiracy. Valpreda was sentenced to four years and six months and Gargamelli one year and six months. Bagnoli was given a two year suspended sentence for criminal conspiracy; Merlino was cleared on grounds of insufficient evidence, but got four years and six months for criminal conspiracy.

The treatment doled out to Valpreda’s relations— who had supported the anarchist’s alibi — was somewhat ambiguous and the perjury charge was thrown out. The same line was taken with Delle Chiaie. And what of Elena Segre, Valpreda’s friend, who had also confirmed the anarchist’s alibi? She had vanished from the records. Another mystery.

The findings handed down in Catanzaro amounted to a contradictory sentence: it recognised the guilt of Freda, Ventura and Giannettini, but was still partly rooted in the case prepared by Judges Occorsio and Cudillo — hence the decision to dismiss the case against the anarchists and conspiracy convictions on the basis of insufficient evidence.

But something else cast an ambiguous light on the verdict. Faced with reticence on the part of some of the VIP witnesses, the judges in Catanzaro opted not to take action themselves, and referred the trial records relating to ex-premiers Giulio Andreotti and Mariano Rumor, and former ministers Mario Tanassi (Defence) and Mario Zagari (Justice) back to Milan. The judges did, however, have grounds for pride in the contradictions into which General Saverio Malizia, Tanassi’s legal adviser, blundered and had him arrested in the courtroom. He was tried immediately and sentenced to one year, but was soon released. This was followed by the usual outcome — the Court of Cassation annulled the trial and referred the case to the Court of Assizes in Potenza who cleared Malizia on all counts on 30 July 1980.

To the aid of the politicians came the judge from Milan, Luigi Fenizio (to whom the investigation had passed when Alessandrini was killed by members of the underground Prima Linea organisation on 29 January 1979) who forwarded an order declaring their innocence to the parliamentary commission of inquiry. On 24 August 1981 the commission closed the file on the accusations against Andreotti, Rumor, Tanassi and Zagari and all four politicians were dropped from the investigation.

But the real sensation came at the appeal hearing when, on 20 March 1981, the Catanzaro court cleared the fascists and the anarchists on the count of massacre. So now no one was to blame for the Piazza Fontana. Freda and Ventura were sentenced to 15 years for conspiracy to subvert and for the bomb attacks of 25 April 1969 and 9 August 1969. In effect, the judges unpicked the logical continuity — underpinned by the evidence — which linked the three main 1969 attacks. They absolved Giannettini on grounds of insufficient evidence and reduced the sentences passed on Maletti and Labruna.

The court of Cassation had this in mind when, on 10 June 1982, it entrusted a second appeal to Bari, to put paid once and for all to the proceedings against Giannettini, who was able to announce: “The implication of myself was prompted by political motives. The intention was to strike at the SID through me.”

The same ritual was played out in the appeal court in Bari (Puglia) — with one outstanding difference: the prosecutor, Umberto Toscani, asked that Valpreda be found not guilty. But the judges chose to stick with tradition: doubt should serve the fascists as well as the anarchists. Meanwhile, they reduced Maletti’s sentence — who was on the run in South Africa — to one year, and that of Labruna to ten months.

With that verdict on 1 August 1985 the curtain was to be brought down on the Piazza Fontana massacre. The final act came in the Court of Cassation in Rome, which rejected every application for a new trial (the Cassation was in fact the central prop of this courtroom farce). It was the highest levels of the judiciary that had taken the initial investigation away from Milan and entrusted them to Rome. They were the ones who had argued that Milan was ungovernable and that the trial should be heard in Catanzaro. They had also conjoined the cases against the anarchists and the fascists.

On 27 January 1987, the first section of the Court of Cassation put paid to a trial that had spread out to occupy time and space. It was Judge Corrado Carnevale (who was later to earn fame as the “verdict-quashing judge”) who was in charge of the most important section of the Court of Cassation and who distinguished himself as the “king of the nit-pickers”, who put Mafiosi, terrorists and bankrupts back on the streets.

Here are a few examples of this: on 16 December 1987, Carnevale annulled the Italicus massacre case, the main accused in which were the neo-fascists Mario Tuti and Luciano Franci. Earlier he had repealed the life sentence passed on the Greco brothers who had been found guilty of ordering the murder of Judge Rocco Chinnici. On 25 June 1990 Carnevale repealed the life sentence passed on Raffaele Cutolo, head of the mafioso Nuova Camorra Organizzata. He also cleared Licio Gelli, on 15 October 1990, on charges of subversion and membership of an armed gang. On 5 March 1991 he ordered a retrial in the case of the 24 December 1984 bombing of the Naples-Milan express in which 16 people were killed and hundreds injured. The upshot of this was the repeal of the life sentence passed on mafia boss Pippo Calò. Such frantic activity could scarcely pass unremarked and in 1995 Judge Carnevale’s performance was the subject of a book, La giustizia è cosa nostra (Justice is Our Thing).

Carnevale has repealed 134 life sentences — 19 of which were passed on the mafioso Mommo Piromalli — plus 700 years’ imprisonment for 96 people charged with mafia membership, drug-dealing and murders.

In short, now the massacre was the subject of new court proceedings following the arrest of Delle Chiaie, Carnevale was the very man for the Piazza Fontana case. And so, on 26 October 1987, the seventh trial relating to the Piazza Fontana massacre — not counting the two aborted by the Court of Cassation — opened with Delle Chiaie and Massimiliano Fachini together in the dock. After 90 sittings, both men were cleared of involvement on 20 February 1989, a verdict confirmed by the Court of Appeal on 5 July 1991