Gladio (Italian section of the Clandestine Planning Committee (CPC), founded in 1951 and overseen by SHAPE (Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers, Europe)

1969

25 April — Two bombs explode in Milan: one at the FIAT stand at the Trade Fair and another at the bureau de change in the Banca Nazionale delle Communicazione at Central Station. Dozens are injured but none seriously. Anarchists Eliane Vincileone, Giovanni Corradini, Paolo Braschi, Paolo Faccioli, Angelo Piero Della Savia and Tito Pulsinelli are arrested soon after.

2 July — Unified Socialist Party (PSU), created out of an amalgamation of the PSI and the PSDI on 30 October 1966, splits into the PSI and the PSU.

5 July — Crisis in the three-party coalition government (DC, PSU and PRI) led by Mariano Rumor.

5 August — Rumor takes the helm of a single party (DC — Christian Democrat) government.

9 August — Ten bombs planted on as many trains. Eight explode and 12 people are injured.

7 December — Corradini and Vincileone are released from jail for lack of evidence.

12 December — Four bombs explode. One planted in the Banca Nazionale dell’Agricoltura in the Piazza Fontana in Milan claims 16 lives and wounds a further hundred people. In Rome a bomb explodes in the Banca Nazionale del Lavoro, wounding 14, and two devices go off at the cenotaph in the Piazza Venezia, wounding 4. Another bomb — unexploded — is discovered at the Banca Commerciale in the Piazza della Scala in Milan. Four hours later, ordinance officers blow it up. Numerous arrests are made, chiefly of anarchists. Among those arrested is the anarchist Giuseppe Pinelli.

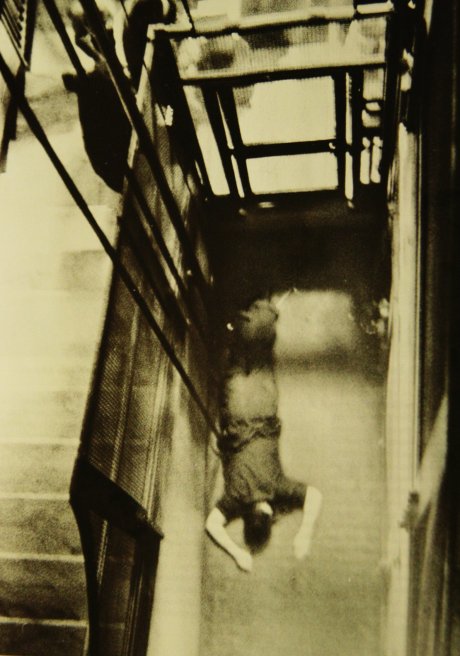

15 December — Anarchist Pietro Valpreda is arrested at the Milan courthouse and taken to Rome that evening. Around midnight, Pinelli ‘falls’ from the fourth floor at police headquarters in Milan.

In Vittorio Veneto, Guido Lorenzon visits lawyer Alberto Steccanella to report that a friend, Giovanni Ventura, may have been implicated in the 12 December bomb outrages.

16 December — Taxi-driver Cornelio Rolandi identifies Valpreda as the passenger he ferried close to the Banca Nazionale dell’Agricoltura in the Piazza Fontana on the afternoon of 12 December.

17 December — Press conference by Milan anarchists at the Circolo Ponte della Ghisolfa. The Piazza Fontana massacre is described as a “State massacre”.

20 December —Nearly 3,000 people attend Pinelli’s funeral.

26 December — Steccanella takes an affidavit written by Lorenzon to the prosecutor in Treviso.

31 December — Treviso prosecutor Pietro Calogero questions Lorenzon.

1970

27 March — Rumor forms a four party government (DC, PSI, PSDI and PRI).

15 April — Inspector Luigi Calabresi begins proceedings against Pio Baldelli, the director of the weekly Lotta Continua who had accused him of responsibility for Pinelli’s death.

21 May — Milan examining magistrate Giovanni Caizzi asks that the file on Pinelli’s death be closed and that it be recorded as an accidental death.

3 July — Antonio Amati, head of Milan CID, agrees to Caizzi’s request to close the file on Pinelli’s death.

22 July — Bomb on ‘Southern Arrow’ train kills 6 and injures 139.

6 August — Emilio Colombo takes the helm of a four party coalition government (DC, PSI, PSDI and PRI).

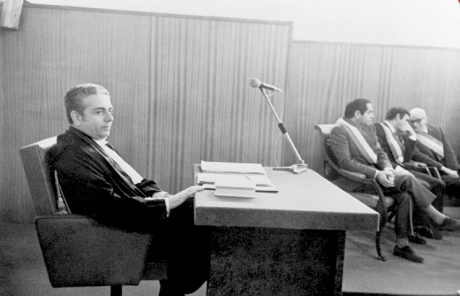

9 October — Calabresi-Lotta Continua case opens. Aldo Biotti, with Michele Lener representing Calabresi, chairs the court. Baldelli’s lawyers are Marcello Gentili and Bianca Guidetti Serra. The prosecution counsel is Emilio Guicciardi.

7 December — Prince Junio Valerio, leader of the Fronte Nazionale, leads an attempted coup d’état. Licio Gelli, head of the P2 masonic lodge, is in charge of kidnapping the president of the republic, Giuseppe Saragat.

12 December — Demonstrations in Milan on the first anniversary of the Piazza Fontana massacre. Fierce clashes between police and demonstrators. Student Enzo Santarelli dies when struck in the chest by a tear-gas canister fired by the police.

1971

13 April — Treviso examining magistrate Giancarlo Stiz issues warrants for the arrest of three Venetian Nazi-fascists: Giovanni Ventura, Franco Freda and Aldo Trinco. The offences alleged against them are: conspiracy to subvert, procurement of weapons of war and attacks in Turin in April 1969 and on trains that August.

28 May — The anarchists tried in connection with the bombs in Milan on 25 April 1969 are acquitted. However, some are convicted of minor offences: Della Savia is sentenced to eight years, Braschi to six years and ten months, Faccioli to three years and six months. Tito Pulsinelli is cleared on all counts. All are freed from jail.

7 June — The Appeal Court in Milan accedes to a request by the lawyer Lener that Judge Biotti be discharged from the Piazza Fontana investigation.

16 July — Death of taxi-driver Rolandi, the sole witness against Valpreda.

4 October — A fresh inquest into Pinelli’s death is held as a result of a complaint brought by his widow Licia Rognini. Milan-based examining magistrate Gerardo D’Ambrosio brings voluntary homicide chargers against Inspector Calabresi, police officers Vito Panessa, Giuseppe Caracuta, Carlo Mainardi, Piero Mucilli, and carabinieri Lieutenant Savino Lograno.

21 October — Judge D’Ambrosio orders Pinelli’s corpse to be exhumed.

24 December — Giovanni Leone is elected president of Italy.

1972

17 February — Giulio Andreotti forms his first government: it is made up exclusively of Christian Democrats.

23 February — Piazza Fontana massacre trial opens in the Court of Assizes in Rome. Judge Orlando Falco presides. The prosecution counsel is Vittorio Occorsio. The accused are Pietro Valpreda, Emilio Bagnoli, Roberto Gargamelli, Enrico Di Cola, Ivo Della Savia, Mario Merlino, Ele Lovati Valpreda, Maddalena Valpreda, Rachele Torri, Olimpia Torri Lovati and Stefano Delle Chiaie. After a few hearings the court declares that it is not competent to hear to hear the case.

4 March — Treviso magistrates Stiz and Calogero have Pino Rauti, the founder of Ordine Nuovo and journalist with the Rome daily Il Tempo, arrested on charges of involvement in the subversive activities of Freda and Ventura.

6 March — Piazza Fontana trial is relocated to Milan.

15 March — Death of publisher Giangiacomo Feltrinelli. His bomb-mangled body is discovered at the foot of an electricity pylon in Segrate, Milan.

22 March — Venetian magistrates Stiz and Calogero indict Freda and Ventura for the Piazza Fontana massacre in Milan.

26 March — The investigation by Stiz and Calogero is passed to the Milan district authorities. It is handled by examining magistrate D’Ambrosio to whom public prosecutor Emilio Alessandrini is seconded.

24 April — Judge D’Ambrosio frees Pino Rauti for lack of evidence.

7 May — Early elections. Rauti is returned as deputy on the MSI ticket. Il Manifesto puts up Valpreda as a candidate but he is not elected.

17 May — Inspector Calabresi is shot dead in Milan.

31 May — A bomb concealed in a car goes off in Peteano (Gradisca d’Isonzo) three carabinieri are killed and one wounded.

26 June — Andreotti remains PM by forming a government with the DC, PSDI and PLI.

13 October — The Court of Cassation transfers the Piazza Fontana case to the Catanzaro jurisdiction.

10 November — A weapons arsenal is discovered in an isolated house near Camerino.

15 December — Parliament passes Law No 733, known also as the “Valpreda Law”.

30 December — Valpreda and the other anarchists from Rome’s Circolo 22 Marzo still in custody (including Gargamelli) are released. Merlino is also freed.

1973

15 January — Freda loyalist Marco Pozzan is smuggled out of the country by the SID.

9 April — Guido Giannettini, Agent Zeta, is smuggled out of the country by the SID.

17 May — Gianfranco Bertoli throws a bomb at Milan police headquarters: 4 people lose their lives and nearly 40 are injured.

7 July — Rumor returns to the government, supported by the DC, PSI, PSDI and PRI.

28 September — Enrico Berlinguer, head of the Italian Communist Party, publishes his first article in the communist weekly Rinascita broaching the “historic compromise”.

1974

14 March — Rumor forms his fifth government with DC, PSI and PSDI support.

28 May — a bomb explodes in Brescia’s Piazza della Loggia during a demonstration organised by the United Antifascist Committee and the trade unions: 8 people are killed and almost 100 injured.

30 May — Federico Umberto D’Amato is replaced as head of the Bureau of Confidential Affairs at the Interior Ministry.

20 June — Giulio Andreotti, Minister of Defence, reveals in an interview with Il Mondo that Giannettini is a SID agent, while Corriere della Sera reporter Giorgio Zicari is an informant.

4 August — A bomb explodes on board the Italicus train on the Rome-Munich line as it passes through the San Benedetto Val di Sambro (Bologna) tunnel, killing 12 people and wounding 48.

8 August — Giannettini surrenders himself to the Italian Embassy in Buenos Aires.

22 November — Aldo Moro forms a DC-PRI coalition government.

1975

27 January — Piazza Fontana case opens before the Court of Assizes in Catanzaro. The accused are: Franco Freda, Giovanni Ventura, Marco Pozzan, Antonio Massari, Angelo Ventura, Luigi Ventura, Franco Comacchio, Giancarlo Marchesin, Ida Zanon, Ruggero Pan, Claudio Orsi, Claudio Mutti, Pietro Loredan, Gianadelio Maletti, Antonio Labruna, Guido Giannettini, Gaetano Tanzilli, Stefano Serpieri, Stefano Delle Chiaie, Udo Lemke, Pietro Valpreda, Mario Merlino, Emilio Bagnoli, Roberto Gargamelli, Ivo Della Savia, Enrico Di Cola, Maddalena Valpreda, Ele Lovati Valpreda, Rachele Torri and Olimpia Torri Lovati.

1 March — Bertoli is sentenced to life imprisonment for the 17 March 1973 bomb attack outside police headquarters in Milan. This sentence is upheld on appeal on 9 March 1976.

27 October — Milan magistrate D’Ambrosio closes the file on the Pinelli death. According to the finding, the anarchist died as the result of “active misfortune”. The ‘misfortune’ resulted in his having fallen out of the window. All those indicted for his death are absolved.

1977

1 October — Freda flees to Costa Rica. He will be arrested and extradited in August 1980.

23 November — General Saverio Malizia, legal adviser to Defence Minister Mario Tanassi is convicted by the Court of Assizes in Catanzaro of perjury and is freed shortly afterwards.

1979

16 January — Ventura flees to Argentina.

23 February — The Catanzaro Court of Assizes returns its first verdict. Freda, Ventura and Giannettini are sentenced to life imprisonment for mass murder, outrages and justifying crime. Valpreda, cleared on the basis of insufficient evidence, is sentenced to four years and six months for criminal conspiracy. Merlino receives the same sentence. Gargamelli is sentenced to 18 months for criminal conspiracy. Bagnoli gets a two year suspended sentence. The perjury charges against Valpreda’s relations and Stefano Delle Chiaie are thrown out; Maletti is sentenced to four years for aiding and abetting and perjury; Labruna gets two years and Tanzilli gets one year for perjury.

1980

4 April — Francesco Cossiga forms a DC-PSI-PRI government.

30 July — The Potenza Court of Assizes acquits General Malizia after the Court of Cassation’s repeal of the 23 November 1977 verdict of the Catanzaro Court.

2 August — Bomb explodes in Bologna railway station killing 85 people and injuring dozens more.

18 October — Arnaldo Forlani forms a four-party (DC-PSI-PSDI-PRI) coalition government.

1981

20 March — The Catanzaro Court of Appeal acquits Freda, Ventura, Giannettini, Valpreda and Merlino on grounds of insufficient evidence. Freda and Ventura are sentenced to 15 years each for conspiracy to subvert the course of justice, for the bombings of 25 April 1969 in Milan and for the train bombs of 9 August 1969. Charges against Maletti and Labruna are dismissed.

28 June — Five-party coalition government (DC-PSI-PSDI-PRI-PLI) forms under Giovanni Spadolini.

24 August — A commission of inquiry drops the charges against Giulio Andreotti, Mariano Rumor, Mario Tanassi and Mario Zagari accused of laying false trails by the SID.

1982

10 June — The Court of Cassation assigns a second appeal case to a court in Bari, leaving Giannettini out of the reckoning.

1985

1 August — The Appeal Court in Bari clears Freda, Ventura, Valpreda and Merlino of the charge of massacre on the grounds of insufficient evidence, but upholds the 15-year sentences on Freda and Ventura, and further reduces the sentences on Maletti (one year) and Labruna (ten months).

1986

1 August — Craxi re-elected as premier of a five-party government.

1987

27 January — The first section of the Court of Cassation, with Corrado Carnevale presiding, rejects all appeals and upholds the verdict passed by the court in Bari on 1 August 1985. Freda, Ventura, Valpreda and Merlino are at last left out of the judicial reckoning.

1988

13 April — Ciriaco De Mita heads a five-party (DC-PSI-PRI-PSDI-PLI) government.

2 July — Leonardo Marino, formerly with Lotta Continua, surrenders to the carabinieri in La Spezia. After 24 days he confesses his guilt to the carabinieri in Milan, naming himself as the getaway driver in the murder of Inspector Calabresi. He also accuses Ovidio Bompressi (another ex-member of Lotta Continua) as the actual killer, and at Adriano Sofri and Giorgio Pietrostefani, the two leaders of that extra-parliamentary organisation, as having ordered the killing.

1989

January — Examining magistrate Guido Salvini launches a new investigation into rightwing subversion and the Piazza Fontana massacre.

20 February — The Catanzaro Court of Assizes clears Delle Chiaie and Massimiliano Fachini of charges in connection with the Piazza Fontana massacre.

1991

12 April — Seventh Andreotti government, a four-party coalition (DC-PSI-PSDI-PLI).

5 July — The Catanzaro Appeal Court upholds the verdict clearing Delle Chiaie and Fachini of involvement in the Piazza Fontana massacre.

1994

11 May — Silvio Berlusconi forms a centre-right government including the FI, AN, LN and CCD. For the first time in post-war Italy the AN or Alianza Nazionale (formerly the MSI) is in government.

1995

13 March — Judge Salvini orders proceedings to be instituted against Nico Azzi, Giancarlo Rognoni, Mauro Marzorati, Francesco De Min, Pietro Battiston, Paolo Signorelli, Sergio Calore, Martino Siciliano, Giambattista Cannata, Cristiano De Eccher, Mario Ricci, Massimiliano Fachini, Guido Giannettini, Stefano Delle Chiaie, Gianadelio Maletti, Sandro Romagnoli, Giancarlo D’Ovidio, Guelfo Osmani, Michele Santoro, Licio Gelli, Roberto Palotto, Angelo Izzo, Carlo Digilio, Franco Donati, Cinzia De Lorenzo and Ettore Malcangi for involvement in Piazza Fontana massacre.

April — Following the order for proceedings tabled by Judge Salvini, Grazia Pradella and Massimo Meroni are appointed prosecution counsel. D’Ambrosio is to supervise them.

1996

17 May — Romano Prodi forms a centre-left government including the PDS, PPI, RI, and UD, the Greens and supported from without by the RDS. For the first time in post-war Italy (since the governments in the immediate post-war years) the Democratic Left Party [PDS], formerly the PCI, is in government.

1 August — Death of Federico Umberto D’Amato, former chief of the Bureau of Confidential Affairs at the Interior Ministry.

4 October — Acting on behalf of Judge Salvini, the expert Aldo Giannuli finds 150,000 uncatalogued Interior Ministry files in a cache on the Via Appia on the outskirts of Rome.

1997

22 January — Sofri, Pietrostefani and Bompressi are finally convicted of killing Calabresi (this is their sixth trial) by the Court of Cassation and sentenced to 22 years in prison. Charges against Marino are thrown out.

2000

5 October — The Court of Cassation throws out the application for a review of the trial that led to Sofri, Pietrostefani and Bompressi being sentenced to 22 years in prison. It closes the ‘Sofri Case’ and marks the launch of a campaign for clemency.

11 March — Milan’s fifth court of assizes sentences Carlo Maria Maggi, Francesco Neami, Giorgio Boffelli and Amos Spiazzi to life imprisonment for their part in the bomb attack at Police HQ in Milan on 17 May 1973. Gianadelio Maletti is sentenced to 15 years for destroying and concealing evidence.

28 November — death of Gianfranco Bertoli.

2002

30 June — Milan’s second court of assizes sentences Delfo Zorzi, Carlo Maria Maggi and Giancarlo Rognoni to life imprisonment for the Piazza Fontana massacre of 12 December 1969. Stefano Tringali is sentenced to three years for aiding and abetting. Pentito Carlo Digilio receives a mandatory sentence.

7 July — death of Pietro Valpreda.

27 September — Appeal court Carlo Maria Maggi, Francesco Neami, Giorgio Boffelli and Amos Spiazzi of the 17 May 1973 bomb attack on Milan police HQ. Gianadelio Maletti’s conviction is overturned.

2003

11 July — The Court of Cassation reverses the acquittals of Carlo Maria Maggi, Francesco Neami and Giorgio Boffelli, and orders a fresh appeal hearing in relation to the attack on Milan police headquarters on 17 May 1973. Amos Spiazzi and Gianadelio Maletti are finally absolved and acquitted.

2004

12 March — Milan court of appeal overturns the verdicts of 30 June 2001 which sentenced Delfo Zorzi, Carlo Maria Maggi and Giancarlo Rognoni to life imprisonment for the Piazza Fontana massacre. Now nobody is to blame for that massacre. Not even these three neo-nazi relics. Nobody planted the bomb in the Banca Nazionale dell’Agricoltura. We need scarcely be surprised. The first verdict, back in 2001, came as a surprise, as did the first verdict in Catanzaro. The verdict of 23 February 1979 that — for that first crime — passed life sentences on Franco Freda, Giovanni Ventura and Guido Giannettini. Those two verdicts were, in fact, an anomaly. If, as I believe I have shown, Piazza Fontana was a state massacre, why on earth would the state want to sit in judgment on itself? Let alone the actual perpetrators? The Ordine Nuovo and Avanguardia Nazionale militants were the witting-unwitting pawns in a game bigger the one that they were playing. The neo-Nazis wanted to change the social and political order in order to introduce an authoritarian, hierarchical regime that would make a clean sweep of “bourgeois democracy”, whereas those in power wanted to cling to that power, not hand it over to the Left. It will be a topic of conversation again in a few years, once nearly forty years have gone by since the massacre. By then it will be nothing but history. Revised and amended, in accordance with the dictates of the revisionism that now rules the roost. However, the verdict from the Milan appeal court contains some spectacular contradictions. First, there is the crude contradiction. At the first trial, Stefano Tringali was sentenced to three years for aiding and abetting; now his sentence has been reduced to one year. How can he still be guilty of aiding and abetting when the main accused have been acquitted? What aiding and abetting could he possibly have done if no crime was committed?

A mystery, one of the many mysteries created by the Italian judiciary. In essence, Milan’s magistrates have declared that the pentito Carlo Digilio is an unreliable witness because he has repeatedly contradicted himself and made mistakes. True he has made some — after suffering a stroke that has left him somewhat impaired — whereas the other pentito, Martino Siciliano, is to be heeded, even though he has supplied “hearsay” evidence which cannot be used for the purposes of trial. A pity no notice was taken of the fact that the magistrate who laid the groundwork for this trial, Guido Salvini, did not draw the line at the evidence laid by the pentiti but looked for — and found — specific confirmation of what Digilio and Siciliano had been saying. It wasn’t enough that Zorzi (initially defended by Gaetano Pecorella, chairman of the Chamber of Deputies’ Justice Commission, a man who also defended Silvio Berlusconi), had repeatedly threatened and plied Siciliano with bundles of cash to retract. Siciliano was, in fact, a “wavering” pentito, but in the end, in the courtroom, he confirmed each of the charges. That was not enough. The acquittal of the trio underlines the old formula of insufficient evidence — which formally no longer obtains. The Milan judges then tacked on this real “gem” in explaining the reasoning behind their acquittal verdict. Retracing the sequence of the 1969 outrages, they concede that Giovanni Ventura and Franco Freda may well have been behind the Piazza Fontana bombing and not just the bomb attacks of 25 April in Milan and the train bombings on 9 August, for which they had already been sentenced to 15 years. The last laugh came in Milan. The two culprits identified by the Treviso investigating magistrate – Giancarlo Stiz (See Chapter 15 – On the Trail of the Fascists) could be the real culprits even though there is insufficient proof of their connections with the Ordine Nuovo group in Venezia-Mestre and Milan. However, there is this small detail: Freda and Ventura were finally acquitted on 1 August 1985 and thus could not be charged with that offence.

Then (years ago) the upper echelons of the Italian state — the Christian Democrats and Social Democrats, who for years have effectively been working in cahoots with the Italian and American secret services (using rightwing extremists as their cohorts) in order to preserve the status quo in Italy, even at the price of bombs and outrages — were dropped from the case. Pietro Valpreda died on 7 July 2002. So many other protagonists are now dead too, and many of their confederates have also left the stage. Developments in the case have been followed vaguely by leading newspapers, and it was only the acquittal verdict that was given any real prominence. No one is to be guilty of the “mother of all outrages”. That is how “reason of state” wants it to be. Luckily, there are some who refuse to play ball. Every 12 December many thousands of 15-18 year old students demonstrate in so many squares around Italy and in Milan, and the Milan procession ends in the Piazza Fontana. That outrage remains an indictment of the criminality of the powers that be. What may be covered up in the courtrooms is “fact” for many. Very many — that has to count for something.

VIDEO LINKS:

LA STORIA SIAMO NOI

9: The role of the United States

THE BLACK ORCHESTRA (1-9)

GLADIO

Episode 1: The Ring Masters 1992

Episode 2: The Puppeteers 1992

DIARIO DI UN CRONISTA — TERRORISMO NERO

Diario di un cronista – Terrorismo nero – parte 1

Diario di un cronista – Terrorismo nero – parte 2

Diario di un cronista Terrorismo nero parte 3

PIAZZA FONTANA: Una strage lunga quarant’anni.

Piazza Fontana – Strategia della tensione (magistrato Pietro Calogero sulla strage di Piazza Fontana 12 dicembre 1969)

ANNI SPIETATI

Anni spietati – Milano – prima parte (69)