When the Milan anarchists from the Ponte Della Ghisolfa circle accused the Interior Ministry of covering up for those guilty of the Piazza Fontana massacre at their press conference on 17 December 1969, the reporters present were incredulous and scoffed. They wrote about “youngsters reeling from the shock of recent days”. But the facts have shown that that accusation was not without foundation.

In fact, we need to take a much closer look at what was being done in the 1960s and 1970s by the Interior Ministry’s Bureau of Confidential Affairs, a powerful security-cum-espionage centre run by Federico Umberto D’Amato. Born in Marseilles in 1919 of a Piedmontese father and Neapolitan mother, D’Amato had risen to prominence in his youth when, in 1945, he had handled contacts with the intelligence services of the Salò Republic to recover the archives of the OVRA (Organization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism), Benito Mussolini’s secret service. He joined the Viminale in 1957 as an ordinary official and rose through its ranks to head the Bureau of Confidential Affairs.

D’Amato was replaced on 30 May 1974, following the slaughter in Brescia, but he stayed on at the Viminale and in fact still controlled the bureau — just as he did when his formal superiors, Elvio Catenacci and Ariberto Vigevano were the directors.

He was obliged to retire in the mid-1980s, moving a lot of important secret files built up over decades abroad. These were tangible evidence of the power he had wielded over many Italian politicians, entrepreneurs, senior managers and intellectuals. But D’Amato was not just a super-spy — he was a man who appreciated the delights of the table and it was in that capacity he edited the weekly food column ‘La tavola’ in L’Espresso and the Guide to the Inns and Restaurants of Italy, published by the same paper. His passion for wine and good food caused his cirrhosis of the liver, and he died in August 1996.

When the student revolts erupted in 1968, D’Amato — who described himself as a sbirro (a plod) but was in fact a skilled double- and even triple-dealer and never let an opportunity go a-begging — was not worried about “students playing at revolution”. His target was, as ever, the Communist Party.

It was his idea to commission the publishing of thousands upon thousands of pro-Chinese leaflets, which he entrusted to Stefano Delle Chiaie for distribution through Avanguardia Nazionale and Ordine Nuovo members. The latter stuck them up on walls in nearly every town in Italy. By providing a helping hand to the PCI’s main competition on the left, D’Amato’s aim was to stir up problems for the largest Communist party in the western world.

But D’Amato’s activities did not stop there. Through his connections with Delle Chiaie and many other Nazi-fascist leaders, he was well placed to manipulate the far-right groups. In practice, D’Amato remotely controlled Delle Chiaie, the Avanguardia Nazionale leader.

The man from the Viminale was also Italy’s representative in the Atlantic Alliance Security Office — NATO’s espionage wing, and was therefore able to control the activities of men such as Carlo Digilio, the quartermaster of Ordine Nuovo’s Venice group and an agent of the CIA and NATO’s security service. It was Digilio who fed Delfo Zorzi with the explosives that were used in the bombs on 12 December 1969. Digilio, a conscientious fellow, reported back regularly to his superiors, as was his duty. D’Amato was, therefore, constantly informed as to the activities of Zorzi, Franco Freda and Giovanni Ventura — as well as being a sleeping partner in them.

So who was ultimately responsible for the Piazza Fontana massacre? And if D’Amato controlled Delle Chiaie, is it conceivable that he was unaware of the latter’s part in the bombings in Rome on 12 December 1969? The idea that D’Amato was implicated is anything but a fantasy, given that the Bureau of Confidential Affairs stepped in to protect the activities of the Freda-Ventura group.

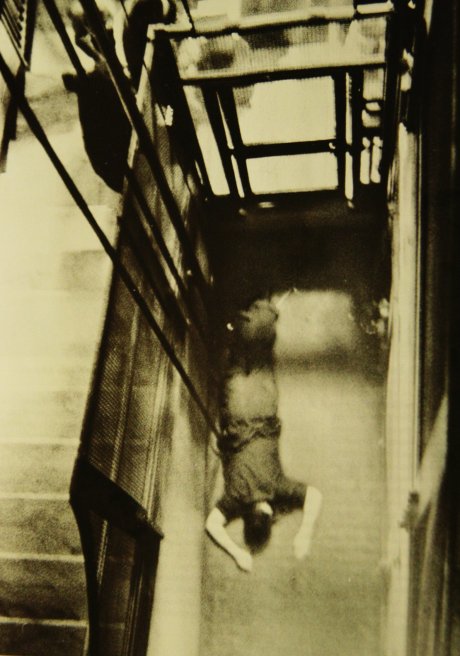

An answer in the affirmative seems convincing. It was Catenacci, who posted flying squad boss Pasquale Juliano far from Padua just as he was about to arrest Freda, before Pasquale could complete his task. It was also Catenacci who immediately after Giuseppe Pinelli’s death — having been promoted to deputy chief of police — conducted a secret inquiry in Milan police headquarters and took evidence from the police officers present at Pinelli’s “flight”.

Then, having given them absolution, he prepared the groundwork for Judge Giovanni Caizzi’s dismissal of the charges against the police. Finally, it was D’Amato, the protector, who allowed Delle Chiaie to go on the run for 17 years.

D’Amato was one of the most powerful men in Italy and it may not have been a coincidence that the famous 150,000 files uncovered towards the end of 1996 came to light after his death.

In its strategy of chasing political wild geese and conjuring up false evidence or mounting provocations, the Bureau of Confidential Affairs had a sound ally, but one with whom it had serious differences, as happens in the world of espionage. That partner occupied the Palazzo Barachini, the headquarters of the SID.

General Vito Miceli held the top job at the SID on 18 October 1970, having taken over from Admiral Eugenio Henke who went on to become army chief of staff. In June 1971 General Gianadelio Maletti arrived to take over D Bureau at the SID — its most sensitive department — from Colonel Federico Gasca Queirazza. For top secret operations he established a base under the cover of the Turris Film Company at 235 Via Cecilia, a street off the famous Via Veneto, and it was from these offices that one of his men, Antonio Labruna, head of the NOD, the SID’s operational wing, operated.

When a discernable fascist lead surfaced in connection with the Piazza Fontana massacre and it become increasingly less concealable, the new bosses of the Italian secret services played their role well as misleaders and provocateurs. First they came up with false documents, which they fed to the judges in dribs and drabs. They then cobbled together a larger-scale operation. The carabinieri in Camerino, under Maletti’s supervision, discovered a huge arms dump near that town on 10 November 1972.

The dump contained three categories of weapon: World War Two matériel; a second category intended to give a left-wing signature to the dump — catapults, glass marbles, spray cans, bottles, cork stoppers, paraffin and sulphuric acid — the ingredients for making Molotov cocktails. The last category comprised 25 MK2 pineapple-style hand grenades (US-made), TNT, high-powered explosives (pentrite), an anti-tank mine and detonators, fuses and German-made timers. All accompanied by upwards of 600 blank identity cards and a coded card index.

The day after the discovery an article appeared in the daily Il Resto del Carlino — a newspaper belonging to the Attilio Monti group — over the by-line of Guido Paglia, an Avanguardia Nazionale member who had recently become a journalist. The article claimed that the coded card index discovered in the cache was “incontrovertible proof of the subversive and paramilitary activities of certain leftwing extremist groups”.

But Paglia did not stop there. Even although the coded documents had yet to be examined and deciphered, the reporter seemed to know already that the arsenal belonged to leftwing extremists from Rome, Perugia, Trento, Bolzano and Macerata. On 3 January 1973 four left-wingers from these places were charged. The only one missing was the terrorist from Rome.

What was it that led the Carabinieri to these four individuals? The answer was simple, if bewildering. The coded pages (every page was topped by an explanatory key) contained a list of 31 activists from the extra-parliamentary left. But Paglia, however, in a frantic hurry to get his scoop as well as complete his provocation, had jumped the gun somewhat. And knew about things that even the carabinieri were not yet in a position to disclose to him. Furthermore, the owner of the isolated house where the cache had been found had been there only a few days prior to the discovery — and there had been no weapons there at the time.

Briefly, this was the sort of set-up that would collapse even while the charges were being prepared. However, it took until 28 April 1976, three years later, for the matter to be brought to closure, with a postscript in the Macerata Court of Assizes when the Ancona prosecutor-general challenged the dropping of the charges. The accused’s dealings with the courts finally ended on 7 December 1977 when they were cleared on all counts.

Meanwhile, light was being shed on the roles of Labruna and especially of Captain Giancarlo D’Ovidio, commander of the Camerino carabinieri who was to move on to the SID’s D Bureau. They were put in the frame by secret service Colonel Antonio Viezzer, a P2 member, on trial for passing secret material to Licio Gelli.

The Labruna-D’Ovidio trail came to nothing, the examining magistrates having dropped the charges on the basis of legal arguments that many other jurists regarded as irrational.

But, in 1993 further significant evidence came to light regarding D’Ovidio’s role as the organiser of this provocation and the part played by Guelfo Osmani, an SID “asset”. The Camerino affair, while it failed to have the effect the secret services had been looking for, it at least generated serious differences and divisions within far left groups with, for example, Italian Maoists being accused of “adventurism”. General Maletti jotted down, in his own hand, in the margins of the report on Camerino the comment: “Good result”.

Soon afterwards, Maletti’s men faced even more taxing missions because their involvement in the 12 December 1969 bombings; lots of other terrorist activities were about to emerge into the harsh light of day.

In January 1973, Freda loyalist Marco Pozzan fled to avoid an arrest warrant issued by the Treviso magistrates. Massimiliano Fachini, who had overseen so many operations on behalf of his comrade Freda, contacted D Bureau. Fachini was well known and Pozzan vouched for him and accompanied the fugitive to the offices of the Turris Film Company in Rome where he was met by Labruna and Guido Giannettini.

Labruna took Pozzan under his wing and had a false passport made out for him in the name of Mario Zanella (a name that turns up in the list of members of the P2 masonic lodge). On 15 January, Labruna escorted Pozzan to Fiumicino airport where he handed him over to maresciallo Mario Esposito and the pair travelled to Madrid. On arrival in the Spanish capital, Esposito took back the false passport and flew back to Italy.

In March 1973, Giovanni Ventura was in Monza prison being questioned by the Milan judges Gerardo D’Ambrosio and Emilio Alessandrini. Ventura was looking for a way out and was beginning to confess. The easiest solution was an escape, something Maletti left to Giannettini to organise. Delfo Zorzi told Carlo Digilio to help Giannettini arrange Ventura’s escape: “Arrange for him to escape. Otherwise Ventura is going to talk.”

Agent Zeta, Giannettini’s code name, contacted Ventura’s sister, Mariangela and his fiancée, Pierangela Baretto and persuaded them his escape plan would work. He gave them two keys that — as was later established in court — opened the prison doors. He also gave them two cans of spray, which the D Bureau had obtained from a firm in Berne to dope the guards.

Once out of prison, Ventura was to be smuggled out to Spain, but he did not trust Giannetini, fearing perhaps that his real destination was not Madrid but that he was to be eliminated once and for all during the breakout. But that was not the end of it; he would escape later, on 16 January 1979, during a stay in Catanzaro, when things were better organised.

Giannettini’s turn came in April 1973. Agent Zeta, a SID officer since 1966 who operated under the cover of journalist, was now firmly in the sights of Judge D’Ambrosio who had been pressing the SID, unsuccessfully, for information about Giannettini. The latter, a key contact between the secret services and the Freda-Ventura group could not afford the luxury of answering questions that would hold his role up to scrutiny, so he chose to go on the run.

Using the SID’s “travel bureau” he slept overnight in the Turris film company’s apartment and was escorted out of the country the following day by the ubiquitous maresciallo Esposito. But with one difference, on 9 April the pair stopped off in Paris where Giannettini was due to fly on to Madrid, and from there to Buenos Aires.

He escaped just in time. The Milan magistrates had Giannettini’s Rome apartment searched in May and a warrant was issued for the arrest of Agent Zeta in January 1974.

Before leaving France, Giannettini gave an interview to journalist Mario Scialoja from L’Espresso in the spring of 1974 to let his bosses know how loyal he was (in case they abandoned him to his fate). He stated: “The sole aim behind naming me as a SID agent is to implicate military circles, especially the SID, in the Freda case. I will have no truck with this gambit.”

But events were moving quickly. In an interview published in the 20 June edition of Il Mondo, Giulio Andreotti told journalist Massimo Caprara that Giannettini was an SID agent and that Corriere della Sera reporter Giorgio Zicari was an established informant. That was a direct signal to Giannettini that he should no longer feel safe — not even in Buenos Aires.

On 8 August Giuseppe Derege Thesauro was made Italy’s ambassador to Argentina. At the Catanzaro trial the diplomat declared: “Giannettini did not hide it from anybody at the embassy that he was running scared and required protection.” Brought back to Italy, Giannettini stuck to his tactics to the end and refused to talk. He made vague allusions by way of signals to his superiors that he would keep mum as long as they stood by him. Hence the statements and depositions from SID chiefs and ministers hell bent on playing down Agent Zeta’s record — the man who had kept them informed about the terrorist activities in which he participated along with Freda and Ventura.

The gamble paid off and the puppet-masters behind the outrages threw Giannettini a few crumbs to stop him talking. He was rewarded for his silence when the Court of Cassation finally dropped proceedings against him in 1982. But he was not left unemployed for long, being taken on by the rightwing financier and publisher Giuseppe Ciarrapico.